-

陈明

2010-07-02 20:381957A 'Death in Venice' by Thomas Mann 的链接地址,这里就不转了.

这个是柯胡特的第一篇论文,他很多后期的思想都能从这里找到痕迹.

-

《魂断威尼斯》 下载http://www.ccs8.cn/forum.php?mod=redirect&goto=nextoldset&tid=8191

魂断威尼斯视屏 http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XMTIxMzU4NzEy.html

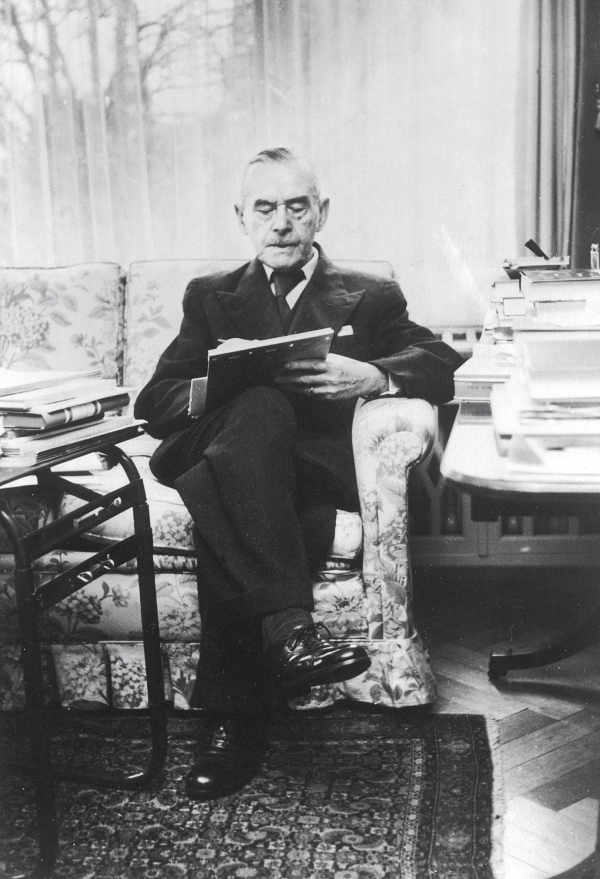

托马斯·曼http://baike.baidu.com/view/75292.htm[本话题由 陈明 于 2010-07-03 15:47:18 编辑]

-

刚看到P210有这句话

Aschenbach's progressive disintegration appears to be based on the fact that he has no object-libidinal ties to reality.

看来阿申巴赫(亞申巴哈)逐步的解体是基于以下的现实:没有客体原欲的链接。

自体客体这一概念大概是从这里来的。

-

p222

On the whole, however, it remains true that the destructive impulses toward Tadzio are secondary, arising only in so far as the narcissistic identification with the boy and the enjoyment of love by proxy are not entirely successful.

对于Tadzio毁灭性的冲动显然是次发的,仅会发生在:自恋式的自居于这个男孩,而且这种通过代理的爱不能够完全成功之时。

这里有自恋暴怒 narcissistic rage,有次发。

-

自恋暴怒等同于代替,

《自我与本我》

“Since the enmity cannot be gratified there develops an identification with the former rival. The study of mild cases of homosexuality confirms the suspicion that in this instance, too, the identification is a substitute for an affectionate object-choice which has succeeded the hostile, aggressive attitude.”。“由于敌意不能令人满意,使发展了一种以从前对手的认同作用。研究同性恋的温和情况进一步证实了这种怀疑,即在这个例子中,认同作用也替代了继敌意、攻击性态度之后的深情对象一选择。”

参见李孟潮的《认同与代替》

客体关系与自体心理学的不同在于,自体提供了一个客体原欲的链接——tied with object-libidinal

-

次序如下:

1)与客体链接失败; 原发过程

2)发展出自毁冲动; 内投

3)冲动指向外部客体; 病理性投射,NPD大概是这个功能没有,所以自体不讲对质,讲镜映。

4)敌意不能满足; 二次伤害

5)代偿性认同替代敌意+温柔的一刀; 内化+防御形成

-

'Death in Venice' by Thomas Mann— A Story about the Disintegration of Artistic Sublimation

托马斯·曼的《魂断威尼斯》:一个有关艺术升华的崩溃故事

Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 26:206-228

Heinz Kohut, M.D.

SUMMARY

In the preceding essay the attempt is made to establish a correlation between some known biographical data, certain trends in the writings of Thomas Mann, and the plot of his short novel,

A brief version of this paper was first presented in 1948 in a seminar on Psychoanalysis and Literature conducted by Dr. Helen V. McLean at the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis.

- 206 -

Death in Venice. The influence of unconscious guilt and, possibly, the role of early sexual over stimulation for the development of an (ironical) artistic personality are discussed. The disintegration of the creative processes in the principal character of the story is seen as a return of unsublimated libido under the influence of aging, loneliness, and guilt over success. It is assumed that the author displaced his personal conflict on the protagonist of the story and thus was able to safeguard his own artistic creativity.

Thomas Mann was born in Lübeck in northern Germany in 1875. His father, a senator and vice-mayor of this old Hanseatic city, died, comparatively young, of septicemia, when Thomas Mann was fifteen. The mother was born in Rio de Janeiro. Her father was a German planter, her mother a Brazilian of Portuguese and Indian stock. After the early death of her mother she was, at the age of seven, taken to Lübeck where she remained. In her youth she was considered to be very beautiful, though for northern Germany a foreign, exotic, southern type. Thomas Mann was the second of the five children of these parents, of whom the eldest, Heinrich, became well known as a novelist.

Thomas Mann's early childhood seems to have been influenced mainly by women. As the family was well-to-do, summers were spent on the shores of the Baltic. He remembers that he dreaded to go back to the city when the summer was over. He hated school and the discipline which it imposed on him during the winter. During his school days he had a homosexually tinged 'crush' for a classmate, apparently the boy Hippe later described in The Magic Mountain.

His first major work, Buddenbrooks, was written in Italy in 1901. He records that he burned his hand severely when sealing the parcel containing this manuscript to send it to the publisher. As there was compulsory military training in Germany, he was to have been inducted into the army. After being twice rejected because of cardiac neurosis, he was finally accepted. Three months later he was given a medical discharge because of an inflamed tendon.

- 207 -

In 1905, at the age of thirty, he married Katja Pringsheim, the only daughter of an old, respected German-Jewish family. His marriage was apparently a very happy one. Of his six children, the youngest girl, Elisabeth, became her father's favorite. In 1910, one year before Death in Venice was written, his sister Carla committed suicide. The effect on him of this tragic event was great, and many years later he described its detailed circumstances with much emotional vividness in the novel Doctor Faustus (1947). When in 1927梖ive years after the death of his mother梩he other sister, Julia, also ended her life by suicide, Mann, as if to reassure himself, commented: 'It seems that the nourishing love has given more resistance to life to us, the sons, than to the girls'.

Despite this assertion, the doubts remained. Earlier, in comparing himself with his sister Carla, he stated that they were made of similar stuff. Both he and his biographers note a certain 'mental laziness' and a tendency to withdraw into sleep in times of stress. He states that he always reassured himself when he began a new work by telling himself that the task would be short and easy. When he had finished it he superstitiously pretended to himself that it had little value. He closed his autobiography (9) by saying: 'I assume that I shall die in 1945, when I shall have reached the age of my mother'. Even from such slender evidence it is apparent that his rational ego was, in times of stress, forced to surrender to archaic magical beliefs.

Death in Venice was written in such a period of stress, and it is the aim of this essay to try to trace in part how the emerging profound conflicts of the author were sublimated in the creation of an artistic masterpiece. With this purpose in mind we shall first examine the content of Death in Venice. In the English translation the short novel is divided into five chapters, following the earlier German editions. While the author abandoned this division in later German editions, the following abstract adheres to it for the purpose of greater clarity.

In the first chapter, all is not well with the hero, Gustav

1The translation 'walk' for the German 'Spazierengehen' is inadequate; there is however, no exact English equivalent. Spazierengehen is an expression of pointed leisure corresponding to the ride in a carriage of the aristocracy. It is perhaps an imitation of this aristocratic habit by the middle class, on foot.

- 208 -

Aschenbach, an artist and writer, as he struggles to maintain his ability to work. In order to carry on, he has to take refuge in frequent interruptions that restore his strength; therefore, he takes naps in the middle of the day and goes on walks1 to recuperate. The walk on which we find him in the beginning of the story leads him by chance to a cemetery. The reader, however, is given the impression that Aschenbach has reached a destination梩hat something meaningful and preordained is happening. This impression is accentuated by Aschenbach's sudden encounter with a man, the first of a series of men of hidden significance he is to meet in the story.

The seemingly intuitive conclusion reached by the reader that something of mysterious import is involved, here and later, is prepared by the author through one or more of the following devices. First, the man at the cemetery, for example, arrives on the scene with a silent suddenness that creates the impression of an apparition rather than an approach. Second, the intense emotional response that this and the other encounters evoke in Aschenbach is out of proportion to the factual significance that any of them should have for him as a person or to the events portrayed in the story. This is a clever maneuver which allows the reader to discard mystical connotations from the framework of the story itself and attaches the mysticism to Aschenbach. In other words, the writer of the story detaches himself from his hero and describes a man who is emotionally impelled by forces which are beyond his reason or control. This is a technique which is rather characteristic of Thomas Mann's fiction. In his later novels the detachment is enhanced by the more deliberate intrusion of the writer in the form of expressed irony. The third device used in Death in Venice to underline the significance of the various figures Aschenbach encounters is their detailed delineation, which, again, is out of proportion to their ostensible import to the hero or the plot.

Returning to the story, the man in the cemetery is described

- 209 -

as having his chin up, so that his Adam's apple looks very bald in the lean neck. He is red-haired, with a milky, freckled skin. Standing at the top of the stairs leading to the mortuary, he is sharply peering up into space out of colorless, red-lashed eyes. The man has a bold and domineering, even ruthless air, and his lips are curled back, laying bare the long, white, glistening teeth to the gums. Aschenbach has, at first, a vague, unpleasant feeling which suddenly changes to an awareness of such hostility in the stranger's gaze that he hastily walks away. He is then seized by a passionate longing to travel which overcomes him so swiftly that it resembles 'a seizure, almost a hallucination'. He sees a tropical landscape with a crouching tiger ready to jump on him and he experiences terror. The hallucination subsides and his self-discipline transforms his yearning into a reasonable desire for new and distant scenes, a 'craving for freedom, release, forgetfulness'. The emotional events following the encounter with the stranger fall into a sequence: first, panic, and the irrational impulse toward flight; then the repression of this ego-alien, dissociated impulse and its replacement by a reasoned, egosyntonic decision to travel.

The second chapter begins with a description of Gustav Aschenbach's personality and an account of his life. One is soon led to assume that the author is drawing quite consciously from his own biography. Even such a detail as the foreign background of his mother, for example, is only thinly disguised. Aschenbach owes certain foreign traits in his appearance to his mother, the daughter of a Bohemian musician. But there are other traits as well that ring a familiar note to any reader of Thomas Mann's autobiographical essay, especially the description of Aschenbach's struggle against forces within himself that interfere with his artistic creativeness. It sounds like a complaint, near to the author's own heart, when he says of his hero: 'From childhood up he was pushed to achievement?and so his young days never knew the sweet idleness and blithe laisser aller that belong to youth'. But Gustav Aschenbach forces himself to work, despite great inner resistances, and he resorts to certain ceremonials that permit him to keep on producing: 'He began his day with a gush

- 210 -

of cold water over chest and back; then setting a pair of tall wax candles in silver holders at the head of his manuscript, he sacrificed to art, in two or three hours of almost religious fervor, the powers he had assembled in sleep'. Aschenbach's attitude expresses a masochistic pride in suffering. His 'new type of hero' is St. Sebastian who, pierced by arrows, '?stands in modest defiance ?. His style of writing is one of 'aristocratic self-command'; he is '?the poet-spokesman of all those who labor at the edge of exhaustion; of the overburdened, of those who are already worn out but still hold themselves upright; ?who yet contrive by skilful husbanding ?to produce ?the effect of greatness'. We learn that selections from his works are adopted for official use in the public schools and that a patent of nobility was conferred upon him on his fiftieth birthday.

Other aspects of Aschenbach's character are not autobiographyical. After a brief period of wedded happiness his wife had died.2 Aschenbach's married daughter remained to him, but he never had a son. One gets the impression that all these details of Aschenbach's life, including his advanced age, tend to prepare the way for the progressive dissolution of the restraining, reasonable forces in his personality梐lmost as if the poet tried to excuse his hero by showing that there are no responsibilities or strong emotional bonds that would tie him to his old existence.3

Others have noted that the description of Aschenbach resembles in physical, facial attributes the Bohemian composer Gustav Mahler, who had died just at the time when the story was written. A further reference to Mahler is the use of the first name Gustav and perhaps also the introduction of a Bohemian conductor as maternal grandfather (2).

2Mann's wife had to go to a sanatorium because of tuberculosis approximately at the time of the composition of Death in Venice.

3The mechanism here may be compared to dreams of failing an examination which, in reality, one has successfully passed long ago (12). Aschenbach's progressive disintegration appears to be based on the fact that he has no object-libidinal ties to reality. This may have served as a reassurance to Mann who, despite temporary loneliness, felt that he had sufficient emotional closeness to his family to preserve him from Aschenbach's destiny.

- 211 -

In the third chapter the 'reasonable flight' from the man in the cemetery is effected. The reader is still given the feeling of the preordained, the vague impression that reason is helplessly succumbing to infinitely stronger irrational forces; that the man in the cemetery is a power within Aschenbach from which there is no escape through external flight.

Outwardly, however, Aschenbach acts quite rationally. He plans his trip to last only a few weeks, tells himself that he needs relaxation and intends to return refreshed to his work. He plans originally to stay on a small island in the Adriatic; yet, even without considering the title of the story, one gathers that the final destination is elsewhere. And so it happens; the weather is bad, the crowd at the hotel is boring, and suddenly it becomes clear to Aschenbach that Venice is his destination.

The man from the cemetery, however, cannot be evaded by flight. On his way to Venice another apparition appears as if to remind the fugitive of the foolishness of his subterfuges. The man on the trip to Venice is a dandy, loudly dressed, with rouge on his cheeks, a wig of brown hair on his head, and rings on his fingers. When he laughs he shows an 'unbroken row of yellow teeth', obviously false; yet, underneath make-up and costume, and behind the loud laughter designed to feign youthfulness, he is an old man. Aschenbach is 'moved to a shudder' as he watches the disgustingly playful way in which the old man behaves toward his young male companions. He tries to avoid him by moving to the other side of the ship, finally escaping by going to sleep. Aschenbach sees him once more, as the old man is leaving the boat. He is pitifully drunk, swaying, giggling, fatuous; licking the corners of his mouth, he teases Aschenbach with remarks about Venice that sound clearly as if they were concerned with the love for a woman and not for a city. 'Give her our love, will you', he says, 'the p-pretty little dear'?here his upper plate fell down on the lower one), the '?little sweety-sweety sweet-heart?.

Aschenbach's third encounter takes place after his arrival in Venice; it is with a gondolier who takes him, against his will,

- 212 -

directly to the Lido. In contrast to the description of the dandy on the boat, but resembling the man in the cemetery, the gondolier is more fearsome than disgusting. The gondola is 'black as nothing on earth except a coffin'; the man, who is 'very muscular' and has 'a brutish face', mutters to himself during the crossing, and the effort of rowing 'bared his white teeth to the gums'. It occurs to Aschenbach that he might have fallen into the clutches of a criminal; but, as before, he withdraws into passivity when his fear is mounting. He becomes indolent and dreamy, and lets matters take their course. Nothing happens; yet, after Aschenbach's arrival, it becomes evident that his misgivings had not been entirely unjustified: the gondolier is 'a bad man, a man without a license' who is sought by the police.

After the preceding encounters the stage is set and the contrast prepared for what constitutes, in the other sense, the goal of the voyage. Aschenbach is scarcely settled in his hotel when the decisive meeting takes place. The antithesis could not be more extreme. The object of his journey is Tadzio, a fourteen-year-old Polish boy of perfect beauty. He is 'pale', shows 'a sweet reserve', is 'godlike', of 'chaste perfection' and 'unique personal charm'. In contradistinction, the boy's three older sisters are described in a disdainful, superior, and almost pitying way. Tadzio is overwhelmingly the favorite of his mother and his governess as revealed by his beautiful attire and by his 'pure and godlike serenity'. The sisters, on the other hand, are dressed with 'almost disfiguring austerity'; 'every grace of outline was wilfully suppressed', and their behavior was 'stiff and subservient'. Aschenbach concludes that the boy is '?simply a pampered darling ?the object of a self-willed and partial love ? from the side of the mother. It is significant, in terms of narcissistic fulfilment, that the major emphasis is on the child. No father is present or implied. The mother's manner is described as 'cool and measured'. She has the '?simplicity prescribed in certain circles whose piety and aristocracy are equally marked'. Something 'fabulous' about her appearance is attributed to pearls, the size of cherries.

- 213 -

Gustav Aschenbach is at first not aware of the impression which Tadzio has made on him. Preconscious signals of anxiety, however, follow directly. He feels tired, has 'lively dreams' during the following night, and is, in general, 'out of sorts'. He blames the weather for his 'feverish distaste, the pressure on the temples, the heavy eyelids'; and considering the possibility of not remaining in Venice, he does not unpack his luggage completely. But all the self-deception is in vain; the fascination is growing. He observes Tadzio innumerable times, at first through chance encounters, later, as his defenses give way, by passionately following him whenever he can; yet he never speaks to him; he remains always alone.

In the engulfing passion for Tadzio there is also expressed a love for the sea which is paraphrased as a 'yearning to seek refuge ?in the bosom of the simple and vast, ?for the unorganized, the immeasurable, the eternal梚n short, for nothingness'. Both appear to Aschenbach as one梩he perfection of Tadzio's beauty and 'nothingness ?[which is] ?a form of perfection'. He observes that Tadzio's teeth are imperfect, and with a pleasure which he does not try to explain to himself he concludes that the boy is 'delicate' and that he will 'most likely not live to grow old'.

Aschenbach does not give up the fight without a last effort. Pretending to himself that he must get away from climatic conditions that seem to portend disease, he makes a valiant attempt to escape from Venice and from his growing infatuation but cannot tear himself away. There is the smell of germicides, a hint about the danger of infection, but 'the city's evil secret mingled with the one in the depths of his heart'. Certain rumors, mentioned in the German papers, were officially denied. But, 'Passion is like crime; it does not thrive on the established order ?. Everything within him had been waiting for a chance to turn back, and all the author can do for his hero is to provide him with an excuse which allows him to postpone the moment of recognition for a little.

The moment comes when all pretext is cast aside and, seemingly

- 214 -

with sudden change of mind, he decides to stay, triumphantly and 'with a reckless joy'. 'With a deep incredible mirthfulness' Aschenbach gives in to the regressive disease of his emotions. With the crumbling of his moral and rational defenses there is now no more need and no longer the possibility of his deluding himself about his true motivations. He acknowledges that it was because of Tadzio that the leave-taking had been impossible.

In the fourth chapter, Aschenbach is no longer trying to deceive himself. He has yielded to his passion for Tadzio, and he accepts and enjoys it. He is able to see the boy many times every day. Some of these meetings occur by chance, but mostly they are deliberately and cunningly arranged. The only defenses which Aschenbach keeps to the very end, even in his dreams, are those for which his past as an artist has equipped him best: sublimation and idealization. The sight of the beautiful boy spurs him to philosophical reflections on the nature of beauty. He summons up the memory of an ancient prototype of his love, of Socrates for Phaedrus. He writes an essay on a 'question of art and taste', trying, in this work, to translate Tadzio's beauty into his style. But his defensive struggles are only partially successful and the instinctual forces cannot be entirely desexualized; after finishing his brief work Aschenbach feels strangely exhausted, as if after a debauch.

Tadzio soon notices the extent to which he has caught Aschenbach's attention, and a tacit understanding is established between them. The child's behavior is dignified, yet seductive. When he recognizes the small signs of response, hints of a secret understanding with the boy, Aschenbach's enthusiasm is, at first, well concealed and controlled. A sudden encounter with Tadzio, however, and an unexpected lovely smile almost tear down his last reserve. All Aschenbach can do is to escape into the darkness where he breathlessly '?whispered the hackneyed phrase of love and longing ?impossible in these circumstances, absurd, ?ridiculous enough, yet ?not unworthy of honor even here: \"I love you!\"'.

- 215 -

The final chapter, while continuing the description of Aschenbach's love and the disintegrating effects it has on his personality, deals, in appearance at least, mainly with the influences of an external event, an epidemic of Asiatic cholera which has broken out in Venice. Population and city officials alike try to conceal the news of the spreading disease, knowing well that the foreign travelers will leave if they find out about it. More and more of the visitors, however, discover the alarming truth and depart from Venice. Tadzio and his family, apparently unaware of what is happening, stay on; hence, Aschenbach remains, sensing the sickness of the city to be a fitting frame for the sickness within himself, the passion to which his reasonable self is succumbing. This defeat of reason and control is now nearly complete. One night he presses his head against the door leading to Tadzio's bedroom, 'powerless to tear himself away, blind to the danger of being caught in so mad an attitude'. While he is not detected on this occasion, he has become conspicuous at other times, and he notices more than once that mother and governess find reasons to call the child away from his proximity. His pride rebels feebly at such an affront, but it is no longer a match for his desire.

To Aschenbach's encounters with the man in the cemetery, the dandy on the boat, and the gondolier, there is now added a fourth encounter with a symbolic male figure, a street musician. Many features in the sketch that the author gives us of him strike us as familiar. He is red-haired; 'the veins on his forehead swelled with the violence of his effort'; his gesticulations, 'the loose play of the tongue in the corner of his mouth', and the strikingly large and naked-looking Adam's apple are described as brutal, impudent, and offensive. After cemetery, senile perversion, and the gondola 'black as a coffin', Aschenbach now faces the final symbolic representation of regression and disintegration in the form of a strong smell of carbolic acid, the odor of death.

Although Aschenbach soon knows the whole truth about the

- 216 -

epidemic in Venice, he does not warn Tadzio's mother. He reflects that Tadzio will die soon and this assumption, uncontradicted by his love, even fills him with a strange pleasure.

Toward the end of the story, and just before Aschenbach's death, he has a nightmare. Its '?theater seemed to be his own soul, and the events burst in from outside, violently overcoming the profound resistance of his spirit; ?[leaving] the whole cultural structure of a lifetime trampled on, ravaged, and destroyed'. The emotions which the dreamer experiences are, at first, 'fear and desire, with a shuddering curiosity'. He heard 'loud confused noises from far away' and a howl resembling Tadzio's name.

匟e heard a voice naming though darkly that which was to come: \"The stranger god!\" ?he recognized a mountain scene like that about his country home? The females stumbled over the long, hairy pelts that dangled from their girdles? They shrieked, holding their breasts in both hands; coiling snakes with quivering tongues they clutched about their waists? Horned and hairy males ?beat on brazen vessels ?troops of beardless youths ?ran after goats and thrust their staves against the creatures' flanks, then clung to the plunging horns and let themselves be borne off with triumphant shouts ?his will was strong and steadfast to preserve and uphold his own god against this stranger ?his brain reeled, a blind rage seized him, a whirling lust, he craved with all his soul to join the ring that formed about the obscene symbol of the godhead, which they were unveiling, monstrous and wooden ?they thrust their pointed staves into each other's flesh and licked the blood as it ran down ?yet it was he who was flinging himself upon the animals, who bit and tore and swallowed smoking gobbets of flesh??and in his very soul he tasted the bestial degradation of his fall.

This dream portrays the depth of Aschenbach's spiritual degradation. The downfall of the standards of his waking life, while less drastic, is not less humiliating. What just recently aroused

- 217 -

his contempt when he saw it in another, he now has yielded to, himself.

Soon thereafter the inevitable happens. On one of his walks, trying to follow Tadzio, Aschenbach loses his way. Exhausted from the heat and wishing to refresh himself, he buys and eats some strawberries, 'overripe and soft', obviously the carriers of the deadly germ. Two days later, fatally ill, he learns that Tadzio is about to leave Venice. He sees him once more, on the beach, just before his death. The last impression of the dying writer, symbolizing and idealizing his death, is of Tadzio, who, moving out into the open sea, waves with his hand as if to invite him outward 'into an immensity of richest expectation'.

In the analysis of Mann's novel, which forms the last part of the present essay, the artist's literary work will, in the main, be viewed as an attempt by the author to communicate threatening personal conflicts. The emphasis of the preceding outline of Death in Venice was, therefore, placed on those aspects of the story that appear to contain the most significant unconscious or preconscious patterns. A number of biographical data concerning Thomas Mann which could serve as a basis for establishing a link between the artist and his work have also been stated. Some additional material referring to the specific circumstances under which Death in Venice was written will now be presented.

Death in Venice appeared first in 1912 in the German literary periodical Die neue Rundschau. It had been written a year earlier, in 1911. Thomas Mann was then thirty-six years old. He had been married for about six years. His father had been dead twenty-one years. His mother was living, and his sister Carla had recently committed suicide. Venice, the stage on which the action of the story takes place, had shortly before been visited by the author. The epidemic of cholera and the attitude of the city officials with regard to it were actualities of the then recent past. A more personal connection with infectious disease was the fact that the author's wife had developed tuberculosis in

- 218 -

1911. She was forced to stay at a sanatorium, and Thomas Mann finished Death in Venice while living alone with his children in T鰈z.

As has already been mentioned, the figure of the composer Gustav Mahler has been woven into the story (2). It is tempting to speculate on the reasons that induced Thomas Mann to introduce some of Mahler's features in the creation of his hero. The only manifest connection is the fact that Gustav Mahler's death occurred in 1911, the year in which Death in Venice was composed. One is however led to assume either that there was a personal relation between Thomas Mann and Gustav Mahler, or that an intimate, perhaps intuitive knowledge of Mahler's personality led the author to avail himself of external characteristics where a more profound similarity between Mahler and Aschenbach was to be implied. To establish the reasons for the special significance of Mahler's death would be an intriguing endeavor.4

We have, however, at our disposal important information about another theme which occupied Thomas Mann's attention during the period before the artistic ideas expressed in Death in Venice were fully developed. We know (2) that his original plan was to write about a singular episode in Goethe's life, namely, how the seventy-four-year-old renowned poet had fallen in love with a young girl梐lmost a child by comparison桿lrike von Levetzow, who was then only seventeen. It is well known that Goethe finally was able to submit to the necessity of tearing himself away from his passion. The celebrated trilogy of poems, Die Marienbader Elegie, is an enduring monument to this event in Goethe's life.

4A letter written by Freud to Theodor Reik (11) establishes the fact that Mahler had consulted Freud and was 'analyzed for one afternoon ?in Leyden' less than a year before Mahler's death. Freud alludes to Mahler's withdrawing of libido from his wife and to Mahler's 'obsessional neurosis'. The latter is especially interesting in view of the obsessional features of Thomas Mann, discussed in the present essay. Dr. Bruno Walter, the distinguished conductor, who knew both Thomas Mann and Gustav Mahler intimately, expresses his firm conviction that Mann and Mahler did not know each other personally at any time (Bruno Walter in a letter to the author of December 13, 1956).

- 219 -

As has been pointed out (6), death is a theme which occurs repeatedly in Mann's works. One of the first stories he wrote (at the age of sixteen or seventeen, about a year after his father died) bears the title Death. It is no exaggeration to maintain that in almost all of his subsequent writings death remains one of the principal themes either as an important part of the action or, in a more disguised form, as recurring metaphysical speculation.

It is not only the frequency with which Thomas Mann returns to the theme of death in his work that reveals its importance to the writer. A more specific connecting link with the author are his protagonists who are often manifestly autobiographically conceived, in particular when Mann tells about the life and the problems of artists. It is the attitudes of these fictitious personalities toward life and death which constitute an important source of information about the author who created them. In the story Tonio Kr鰃er, as well as in other early works of Thomas Mann, death, or the sympathy for death, seems to gain its significance not so much from any expressed value of its own but rather from an aristocratic negation of life (6).

Tonio Kr鰃er feels it necessary to divorce himself from life; he can remain artistically active and creative only inasmuch as he ceases to be a human being (6). If an adolescent assumes such an attitude as a defense in his struggle against overwhelming instinctual demands, we are inclined to regard it as temporary. As Anna Freud has pointed out (3), the asceticism of youth has to be considered as a normal phenomenon. The author of Death in Venice, however, was a mature man of thirty-six with a wife and children. The artists in Thomas Mann's stories are influenced by the progress-negating philosophy of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche and subscribe to the creed of the German romanticists that there is a close affinity between beauty and death (8). The romantic artist must be dead, symbolically, in order to be able to create a work of beauty. This tendency is particularly evident in the hero of Death in Venice. The very name, Aschenbach ('brook of ashes'), clearly evokes, at least in the original German,

- 220 -

the association with the river of the dead in classical mythology (5). To enable himself to work, Aschenbach is described as resorting to the ceremonial of placing lighted candles at the head of his manuscript which creates a distinctly funereal impression; in addition he feels compelled to mortify the flesh by self-abnegation and by a strong need to isolate himself (6).

At the time this novel was written, only two important members of the author's family were dead: the father, who had died many years ago, and the beautiful sister Carla, who had recently committed suicide. One is immediately inclined to assume that the identification is with the dead father and not with Carla for the simple reason that the heroes of Thomas Mann's earlier stories are struggling with problems similar to Aschenbach's, and that these stories were written before Carla's suicide. Apart from such negative reasoning, which tends to exclude the sister from consideration rather than to establish the father for the role, there is, it seems, more positive proof to be obtained within the story itself.

The literary commentators (1), (2), (5) are in accord about the fact that the four men whom Aschenbach encounters are messengers of his impending death; and it is plausible to assume that this symbolism was consciously intended by Thomas Mann as he wrote the story. By contrast, the interpretation offered in the present essay is that the four apparitions are manifestations of endopsychic forces, projected by Aschenbach as the repression barrier is beginning to crumble. The four men are thus the ego's projected recognition of the break-through of ancient guilt and fear, magically perceived as the threatening father figure returning from the grave. Three of these four figures, the man in the cemetery, the aged freak on the boat, and the gondolier, are described as baring their teeth in a strange way which has been pointed out (5) as calling to mind the idea of the skull of a skeleton: death or a dead man. The gondolier in a gondola, black like a coffin, seems to be an allusion to the figure of ancient mythology, Charon, who ferries the dead across the River Styx to Hades (2). The first man arises from the cemetery with the

- 221 -

suddenness of an apparition梩he most unambiguous portrayal of someone deceased who threateningly returns. The last one, a street singer, carries about him the odor of death. All except the dandy on the boat are described as powerful and dangerous, and a more or less clear inference of free, unhampered aggression and sexuality can easily be drawn. When we read in the description of the street singer that the veins on his forehead were swollen, we may interpret this detail as an allusion to either or both of the aforementioned standard attributes of a feared father: sexual excitement or rage. The old man dressed up to give the deceptive impression of youth suggests a parallel with a dead man who comes back to life. The varying combinations of fear and contempt which are experienced by Aschenbach in these encounters express the original hostile and loathing attitude toward a father figure with the secondary fear of retaliation from the stronger man; also included is probably the ego's reaction against the emerging superstitious fear of the returning dead, an attempt at self-reassurance by ridicule.

In this context it is illuminating to remember Thomas Mann's confession that he could not free himself entirely from very superstitious attitudes and beliefs. For example, he attached special significance to the date and hour of his birth; certain numbers had a particular magical meaning for him; and the fact that his children were born, as he said, 'in pairs' (girl and boy; boy and girl; girl and boy), constituted for him a lucky omen (9). The coexistence of such superstitious beliefs with extreme rationality is characteristic of compulsive personalities. That the archaic ego of the compulsive is particularly prone to believe in the magical powers of the dead is also a well-established fact.

Another peculiarity of the compulsive personality is the predominance of strongly ambivalent attitudes, particularly toward the father and father surrogates. In this connection, light is shed on Mann's preoccupation with the aged Goethe, who certainly represents the father figure of father figures for any German writer. The ascertained fact that the topic of Goethe's infatuation with a young girl was in the writer's mind just before the

- 222 -

Aschenbach story was taking shape adds, though indirectly, to the evidence for the assumption that the central theme underlying Death in Venice is the father conflict. Reverence for Goethe usually prevents biographers from dwelling on the ridiculous aspects of his last love affair; at most, the tragic impossibility of the liaison is stressed. Both of these opinions are stated in Death in Venice: the latter, in the author's attitude toward Aschenbach's passion for Tadzio ('?impossible in these circumstances, absurd,梤idiculous enough, yet ?not unworthy of honor even here ?); the former, expressing straightforward ridicule and disgust, in the portrayal of the old dandy on the boat.

In general, one can say, that the father theme is dealt with in Death in Venice by splitting the ambivalently revered and despised figure and by isolating the opposing feelings that were originally directed to the same object梐 typical compulsive mechanism. The bad, threatening, sexually active father is embodied in the four men Aschenbach encounters. With the good one, who foregoes threats and punishment and heterosexual love梬ith the father, that is, who loves only the son—schenbach identifies himself, portraying in his love for Tadzio what he wished he had received from his father. This device, however, is not entirely successful: Aschenbach's ambivalence is intensified by the narcissistic, envious recognition that another is getting what he really wished for himself, and hostile, destructive elements enter into his feelings toward Tadzio. He not only experiences a strange pleasure at the thought that Tadzio will die early, but indirectly he also exposes the beloved boy to great danger by not warning his family about the epidemic. On the whole, however, it remains true that the destructive impulses toward Tadzio are secondary, arising only in so far as the narcissistic identification with the boy and the enjoyment of love by proxy are not entirely successful. The basic hostility is not directed against the boy (as jealousy against a brother) but against the hated father image. The ferociousness of this hatred is revealed in Aschenbach's last dream in which his unsuccessful struggle with the bad father, the foreign god of the barbarians,

- 223 -

the obscene symbol of sexuality, the totem animal, is killed and devoured. By the law of talion, which is the immutable authority for the archaic ego of the compulsive, death must be punished by death and Aschenbach has to die.

The decisive threat to Aschenbach's defensive system is, however, neither caused by the traces of envious hostility against Tadzio nor by the hatred against the father but by the breakdown of sublimated homosexual tenderness and the nearly unchecked onrush of unsublimated homosexual desire in the aging writer. Aschenbach's last dream is an expression of the breakdown of sublimation; it describes the destruction of 'the whole cultural structure of a lifetime'.

The material that builds up the dream comes from three sources. First, we can discern remnants of sublimatory ego activity; they account for the formal aspects of the dream which retains something artistic and impersonal as if it were a beautiful fable from classical mythology. Second, we recognize the portrayal of the disintegration of Aschenbach's personality; it finds expression specifically in relation to his now unconcealed sexual desire for Tadzio. The former sweetness of Tadzio's name has been transformed into 'a kind of howl with a long-drawn u-sound at the end'. Third, the undisguised emergence of a primal scene experience allows us to draw conclusions about the traumatic impact of the observation of the sexual activities of adults upon the child.

The sequence of curiosity, mounting sexual tension, wish to participate in the sexual activity, and the fear of being annihilated by participation in the sadistically misinterpreted sexual activity of the adults are clearly described. There is little doubt, too, that the homosexual desires and fears must have originated during such experiences梩hat the child must have been partially identified with the mother and must have wished for the sexual love of the father. The dread of castration (death), aroused by the wish to participate in the violent activity of the adults and, especially, by the passive attitude toward the father, must have led to an attempt to abandon the libidinal striving for participation

- 224 -

and may have initiated the building up of 'the whole cultural structure of a lifetime'.

We may well find the origins of Aschenbach's artistic attitude in the dangers of the primal scene experience. At the beginning of the primal scene the child is an observer, not yet threatened by traumatic overstimulation, passivity, and fear of mutilation. Could it not be that the child, as the dread becomes overwhelming, returns by an internal tour de force to the original role of the emotionally uninvolved observer, and that further elaborations of such defenses against traumatic overstimulation make important contributions to the development of creative sublimation?

To prevent misunderstanding, these considerations are not intended to furnish a complete explanation of artistic creativity, not even to those limits that apply in general to genetic constructions. The hypothesis that artistic creativity may be related to the feminine principle, and that artistic creativity may in certain instances derive its energy from the sublimation of infantile wishes does not need support from the material which has been presented. Suffice it to say that Aschenbach's homosexual organization and feminine identification are fully compatible with this old and well-substantiated psychoanalytic thesis, and that the waxing and waning of artistic productivity in Aschenbach seems to run parallel with the predominance either of the sublimated or of the unsublimated homosexual strivings.

The specific hypothesis that is advanced here refers to certain features of the artistic attitude in an individual instance. Primal scene experiences, creating overstimulation, dangerous defensive passive wishes, and castration anxiety, may lead to the attempt to return to the emotional equilibrium at the beginning of the experience and prepare the emotional soil for the development of the artistic attitudes as an observer and describer. This hypothesis seems particularly compatible with certain qualities of Mann's art, his detachment and irony. It is possible that similar considerations apply, beyond Aschenbach, to other artistic personalities and, more generally, that it is perhaps

- 225 -

a genetic factor in the development of an ironical attitude toward life.

Beyond the portrayal of problems posed by the mother identification and by the ambivalently passive attitude toward the father, the trend toward union with the mother can also be discerned in Mann's writings. This wish, however, is more strongly repressed and seems to evoke even deeper guilt than the ambivalent attitude toward the father. Rarely does it, therefore, reveal itself in a sublimated, egosyntonic form of object love and, if instances of this type occur, they are by no means unambiguous. One might speculate that perhaps the Slavid features of Tadzio (or of Hippe and Claudia Chauchat in The Magic Mountain) contain a hint of effectively sublimated love for the mother who, in real life, was an 'exotic type'. Yet almost always when we encounter the wish for the mother we find it presented either in vague, deeply symbolic terms or in the regressive form of 'identification' rather than as object love. In addition some kind of punishment, mostly in the form of death or disease, is expressed or implied. This holds true not only for Thomas Mann's literary productions but also for his actual beliefs, as can be inferred from his superstitious prediction that his life would come to an end in 1945, when he should have reached the age at which his mother had died.

The wish for the mother expresses itself, more frequently than in the forms discussed above, in even more regressive, diffuse, highly symbolic yearnings. It seems that this is the only way in which this deeply guilt-provoking wish is permitted to occur repeatedly in the consciousness of the writer and of his literary figures and is allowed to be accepted by the ego with a certain degree of pleasure. The pleasure, however, is a rather melancholy one for in many of Thomas Mann's works the wish for the mother emerges disguised as a longing for death. In The Magic Mountain it is the immensity of an alluring snow landscape which attracts Hans Castorp and almost leads to his death by freezing. In Death in Venice the mother symbol seems to be represented first of all by the sick city itself from which Aschenbach

- 226 -

cannot extricate himself; it is not only a city, but also the sea, and death梩he whole atmosphere of Venice, death, and the sea together梩oward which Aschenbach's deepest wishes are directed. As death is overtaking him, Aschenbach sees Tadzio, beckoning him outward into the open sea, 'into an immensity of richest expectation'. This picture, then establishes clearly not only the symbolic identity of death and the sea but also the connection between the boy, Tadzio, and the sea-death-mother motif.

We are faced with the final task of examining the specific circumstances in the author's life that might have activated his conflicts and thus provided the impulse for writing Death in Venice. The recent suicide of the sister Carla, an old competitor for parental love, might have precipitated feelings of guilt. Perhaps, too, Carla constituted an object of strivings which were displaced from the mother to the sister, a speculation that finds support from the fact that Mann treated the incest motif between brother and sister in the short story, W鋖sungenblut, written in 1905 (7).

Of greater importance was probably the concurrent illness of Mann's wife which may have forced the author into closer affectionate ties with his young children. The possibility may also be entertained that his wife's illness may have necessitated a period of sexual abstinence which, in turn, led to increased conflicts concerning homosexual regression.

As we follow the sequence of Mann's publications we can, it seems, discern that, with his increasing success as a writer and with the reassuring stability of his position as husband and father, his original 'sympathy with the aristocracy of death' began to be counterbalanced more and more by an actively participating acceptance of life. This more affirmative attitude toward life finds expression in most of Mann's writings after the first World War (6). Settembrini, in The Magic Mountain, is certainly an advocate of active participation in life and an outspoken enemy of any sympathy with death or disease; and there can hardly be any doubt that the author's conscious affection

- 227 -

was for Settembrini and not for Naphtha, his adversary; yet, the old conflict between progressive and regressive forces was never fully resolved. Mann's preoccupation with death and disease continued to be expressed in his last writings, despite his admirably courageous attitude in the political events preceding and during World War II.

In his preface (10) to a volume of stories by Dostoevski, Mann recognized that he, like the great Russian, received much of the impetus for his productivity from a deep sense of guilt and that, in a way, his literary productions served as expiations. Glover mentions (4) that some obsessional neurotics fear that analysis will destroy their sublimatory capacities and that, in fact, the sublimated activities of the ego are equated with sexual potency by them. One of Mann's lifelong preoccupations was the struggle to maintain his artistic creativity which seemed forever threatened and precarious and which he tried to protect with superstitious magic. Paradoxically, the successful sublimation of passive feminine attitudes into artistic creativity must have called forth the guilt of masculine achievement.5 And like the artist-hero in one of his last novels, Doctor Faustus (1947), who sells his soul to the devil and accepts disease and early death in return for a measure of active living in artistic productivity, Thomas Mann, too, seems to have to assure the threatening father that he has not really succeeded, and that his sublmiations are breaking down. Aschenbach in Death in Venice and Leverk黨n in Doctor Faustus allowed Mann to spare himself, to live and to work, because they suffer in his stead.

REFERENCES

BAER, LYDIA The Concept and Function of Death in the Works of Thomas Mann Philadelphia: Privately printed, 1932

ELOESSER, ARTHUR Thomas Mann, sein Leben und sein Werk Berlin: S. Fischer, 1925

FREUD, ANNA The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense London: Hogarth Press, 1937

GLOVER, EDWARD The Technique of Psychoanalysis New York: International Universities Press, Inc., 1955

HAVENSTEIN, MARTIN Thomas Mann, der Dichter und Schriftsteller Berlin: Wiegand & Grieben, 1927

KASDORFF, HANS Der Todesgedanke im Werke Thomas Manns Leipzig: H. Eichblatt, 1932

MANN, THOMAS W鋖sungenblut Munich: Phantasus-Verlag, 1921 (Privately printed.)

MANN, THOMAS Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen Berlin: S. Fischer, 1918

MANN, THOMAS Lebensabriss In:Die neue Rundschau Berlin: S. Fischer, June 1, 1930 pp. 732, ff

MANN, THOMAS Dostoevski梚n Moderation In:The Short Novels of Dostoevski New York: Dial Press, Inc., 1945 pp. vii-xx

REIK, THEODOR The Haunting Melody New York: Farrar, Straus and Young, 1953

STEKEL, WILHELM Beitr鋑e zur Traumdeutung Jahrb. psychoanalytische & psychopathologische Forschungen I 1909 p. 458

We remember in this context that he burned his hand severely when sealing the package containing the manuscript of the novel (Buddenbrooks) that was to bring him fame, and we recall the ceremonials of magical expiation that characterize Aschenbach's working habits.

-

亚申巴哈 Aschenbach

塔吉欧 Tadzio

关键词:情绪退化 emotional

理想化 idealization

重建功能 restitutive

自体状态的梦 self-state dream

自恋脆弱性 narcissistic vulnerbility

自体客体 selfobject

客体原欲 object-libidinal

趋力-防卫心理学 drive-defense psychology

自恋式认同 narcissistic identification

崩解 fragmentation

复原性理想化 restitutive idealization

自恋暴怒 narcissistic rage

崩解状态 fragmentation states

自体统整性 self-cohesion

你还不是该小组正式成员,不能参与讨论。

现在就加入。