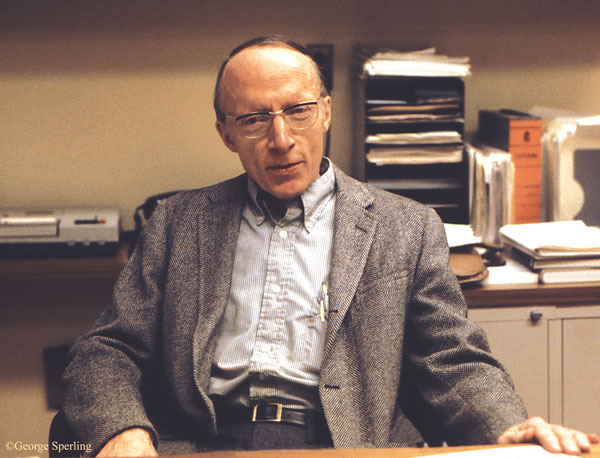

Our friend, mentor, and colleague, Bill Estes, died quietly at the age of 92. His health had declined steadily in the last three months since his wife of almost 70 years, Kay, died in May. Since then he had spoken repeatedly of wanting to join her. As per his wishes, he was cremated and interred with Kay and their son, Greg, in Illinois.

William K. Estes’ long and productive career encompassed the science of learning and memory from behaviorism to cognitive science, with seminal contributions to both. Estes (born June 17, 1919) began his graduate studies under the tutelage of B. F. Skinner during the early 1940s.

The United States had not yet entered World War II. The Germans were using a new technology — rockets — to bomb England. As Londoners heard the whine of the rocket engines approaching, they stopped whatever they were doing — eating, walking, or talking — and waited for the explosions. After the rockets dropped elsewhere and people realized they were safe, they resumed their daily activities. Intrigued by these stories from London, Estes and Skinner developed a new conditioning paradigm for rats that was similar, in some respects, to what Londoners were experiencing. This paradigm, called conditioned suppression, was a new technique for studying learned fear (Estes & Skinner, 1941). Estes and Skinner placed hungry rats in a cage that delivered food pellets whenever the rats pressed a lever. The cage also had a metal grid floor wired to deliver a mild shock to the rats’ feet. Normally, the hungry rats pressed the lever to obtain food; but if the experimenters trained the rats to learn that a tone predicted an upcoming shock, the rats would freeze when they heard the tone and wait for the shock. Measuring this freezing behavior allowed Estes to quantify trial-by-trial changes in the learned response. Within a few years, this conditioned emotional response paradigm became one of the most widely used techniques for studying animal conditioning, and it is still in use today.

As soon as he completed his PhD, Estes was called into military service. He was stationed in the Philippines as the commandant of a prisoner-of-war camp, a not-very-demanding job that gave him lots of free time to read the mathematics books sent from home by Kay. When the war ended, Estes returned to the United States and to the study of psychology. Much to Skinner’s dismay, Estes soon began to stray from his mentor’s strict behaviorism. He started to use mathematics to describe mental events that could only be inferred indirectly from behavioral data, an approach quite unacceptable to behaviorists. Years later, in his autobiography, Skinner bemoaned the loss of Estes as a once-promising behaviorist, speculating that Estes’ preoccupation with mathematical models of unobservable mental events was a war-related injury, resulting perhaps from too much time in the hot Pacific sun (Skinner, 1979).

Estes built on Hull’s mathematical modeling approach to develop new methods for interpreting a wide variety of learning behaviors (Estes, 1950). Most learning theorists of that era, including Hull, assumed that learning should be viewed as the development of associations between a stimulus and a response. For example, suppose that a pigeon is trained to peck whenever it sees a yellow light in order to obtain a bit of food. Hull assumed that this training caused the formation of a direct link between the stimulus and the response and that later presentations of the yellow light would evoke the peck-for-food response. Estes, however, suggested that what seemed to be a single stimulus, such as a yellow light, was really a collection of many different possible elements of yellowness and that only a random subset of these elements are noticed (or “sampled,” in Estes’ terminology) in any given training trial. Only the elements sampled on the current trial were associated with the response. On a different trial, a different subset is sampled, and those elements were now associated with the response. Over time, after many random samples, most elements became associated with the correct response. At this point, any presentation of the light activated a random sample of elements, most of which are already linked with the response.

Estes called his idea stimulus sampling theory. A key principle of the theory is that random variation (“sampling”) is essential for learning, just as it is essential for the adaptation of species in Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution through natural selection (Estes, 1950). Estes’ approach gave a much better account than other theories (such as Hull’s) of the randomness seen in both animal and human learning, and his theory helped to explain why even highly trained individuals don’t always make the same response perfectly every time. On any given trial, it’s always possible that (through sheer randomness) a subset of elements will be activated that are not linked to the response. Estes also showed how stimulus sampling theory explains how animals generalize their learning from one stimulus (e.g., a yellow light) to other, physically similar stimuli (e.g., an orange light), as Pavlov had demonstrated in the 1920s.

Estes’ work marked the resurgence of mathematical methods in psychology, reviving the spirit of Hull’s earlier efforts. Estes and his colleagues established a new subdiscipline of psychology called mathematical psychology, which uses mathematical equations to describe the laws of learning and memory. From his early work in animal conditioning, through his founding role in mathematical psychology, to his later contributions to cognitive psychology, W. K. Estes continued to be a vigorous proponent of mathematical models to inform our understanding of learning and memory

W.K. & K.W. Estes Fund

William K. Estes (June 17, 1919 – August 17, 2011) had an enormous influence on psychological science, from his pioneering work in mathematical psychology to his collaborations with colleagues to his mentoring of students, many of whom are now leaders in the fields of learning and memory. He was recognized for his lifetime of contributions with our nation’s highest scientific honor, The National Medal of Science.

Bill also had a special role in APS’s history and success as Founding Editor of our flagship journal Psychological Science. During those years, his wife, Katherine W. (Kay) Estes, served as Founding Managing Editor. Bill and Kay were a team in so many undertakings. The W.K. & K.W. Estes Fund celebrates their contributions to psychological science.

Make a contribution online atwww.psychologicalscience.org/estes-fund

A downloadable form is also available on that webpage.

-Mark Gluck,

Rutgers University

Henry L. “Roddy” Roediger, III

Washington University

I came to Purdue University in July 1973 as a brand new assistant professor. A few months before I arrived, Bill Estes had visited. I was sorry to have missed the chance to meet him, but I heard a good story about the visit from several sources.

The Purdue Psychology Department had been seeking a big equipment grant for new computers from NSF. At the time I arrived, there was a hulking machine there called a Linc 8 (it nearly filled a whole room) and two PDP somethings, maybe PDP-8s. They had cords spewing out the back, and if any one was misplaced, the whole system failed. At any rate, Purdue psychologists wanted more computers. Bill had come for a site visit, and he led the visiting team. I heard all this second hand, since I was not there to witness the event itself.

The faculty figured they needed to show off the computers doing something, so they hooked them up to slide projectors. What Bill and the site visit team saw were these massive computers making slide projectors advance at the rate of one slide every two seconds, something a work-study student could have accomplished with no trouble.

At the final meeting, after making an impassioned plea for why the Purdue Department needed three more computers, the Purdue faculty finished speaking. It was Bill’s turn to talk. A long, incredible, silence ensued as people waited for some kind of response from the leader of the site visit team. Finally, Bill said “Does that mean you would need three more slide projectors, too?”

NSF did not give Purdue the grant. This story about Estes was told and retold for a while in the Department. I might have heard an embellished version, but probably not. I got to know Bill a little bit years later, but never worked up the courage to ask about the Purdue site visit.

R. Duncan Luce

University of California, Irvine

Bill and I were among the creators of mathematical psychology during the 1950s. One major accomplishment was the creation of the Mathematical Social Science Board (Robert R. Bush, Clyde H. Coombs, Estes, R. Duncan Luce, and Patrick C. Suppes) that raised NSF funding to run modeling workshops at Stanford University during the summer months in the 1950s and 1960s. A second was the founding in 1964 of theJournal of Mathematical Psychology, which was soon followed by the founding of the Society for Mathematical Psychology. Although our careers frequently overlapped, we never wrote a joint paper. My wife and I often saw Bill and Kay socially when we were both in Cambridge, and we have many warm memories of dinners and concert evenings together as well as the Estes’ annual Holiday Open House. I join others in mourning the loss of a giant in the field.

George Collier

Rutgers University

The year I entered the University of Minnesota as a freshman, 1939, was a frenetic year of uncertainties and excitement. I was a putative physics major but never became part of that group. Rather, I hung out with friends from high school — Bill Estes, Paul Meehl, and Norm Guttman — in the psychology department, where the “action” and excitement were. It was a time of politics and revolution, Roosevelt, Hitler, Stalin, Franco, Skinner, Hathaway, and Feigl; it was talk, talk, talk and opinion, opinion, opinion. Kay Walker and Keller Breland, who shared graduate student offices on the third ring of the atrium in the psychology building, held forth loudly and obscenely about the virtues of operant psychology while smoking twisted Cajun cigars that Keller had brought from southern Louisiana. (Kay was shedding her “proper lady” upbringing.) Some students were touting Starke Hathaway’s experimental approach to building a personality assessment (the MMPI), others were arguing the merits of various political outlooks, and so on. There were many very bright grad and undergrad students in that group who went on to become famous. Elliott, the psychology chairman and a very proper Harvardian who had hired Skinner at Boring’s suggestion, must have wondered how he got into such a hornet’s nest. As far as I remember, Bill never participated in the violent discussions, but on our walks about campus, it was clear that he had listened.

(Click image to view larger timeline)

Bill was fiercely, but discretely, competitive. I am sure he greatly enjoyed the single B that Paul Meehl got, but we will never know. Bill was comfortable with his talent and accomplishments and tolerant of others.

Meeting Bill on campus was an experience. We’d often cross paths, traveling in opposite directions. I’d greet him, “Hi Bill,” and after walking on for 20 ft. or more, I’d hear, “Hi George.”

Bill and I took college algebra together — a requirement for all liberal arts majors. It was taught by a young instructor, Howard Herbert Campaigne, who went on to be a famous algebraist. He always interrogated students about solutions to problems during class. Whenever he asked Bill a question, Bill would just sit passively, quiet, no response. This always infuriated Campaigne: “Mr. Estes, you must study!” These encounters diminished somewhat as Bill turned in perfect exam after perfect exam, but the grand climax came one day after Campaigne laboriously wrote a particularly long proof on the blackboard. For the first time, Bill raised his hand. Campaigne, with exaggerated sarcasm: “Well, Mr. Estes, you finally have something to say???” Bill: “Three steps.” Campaigne handed Bill the chalk. Bill went to the board, put up a simple, elegant proof on it, and returned to his seat without a word. Campaigne subsequently asked Bill to shift his major to math. Bill reportedly responded, “Too boring.”

The draft was looming. Skinner saved several students (e.g., Guttman, Breland, etc.) by hiring them on the Pigeon Bomb Project (a World War II project in which Skinner attempted to make a pigeon-guided missile). Bill was originally a clinical doctoral student with Hathaway. I don’t know the arrangements, but his famous thesis research on a clinical-type of problem (quantifying anxiety) was conducted with Skinner. After finishing his degree, Bill went into the Army as a clinician. Other students also stayed at Minnesota to finish their degrees and then joined the Army or Navy. More junior students like me had left college to join Uncle Sam’s guided tour and returned after the war to finish up.

After the war, Skinner was recruited by J. R. Kantor as the ideal behaviorist and became chairman of psychology at Indiana University. He assembled a group of faculty that included Bill Estes, Clete Burke, Bill Verplanck, and Norm Guttman with the goal of establishing IU as the center of operant psychology. He had a large pigeon lab, lots of foot soldiers on the G.I. Bill, and lots of funding. He recruited me as a graduate student but ran out of money before I got there and forwarded me to Bill Verplanck, who had a huge Office of Naval Research grant. Luckily for me, Kay Estes was also in Verplanck’s lab. He had hired her on his grant to organize and run statistics on the voluminous amounts of data on the visual detection threshold that he had gathered while in the Navy. Often I overheard her swearing under her breath, “What a _ _ _ _ _ _ _ mess!” Kay took me under her wing, helping wash away the lingering memories of war by lending an understanding ear, editing and re-editing my ungrammatical write-ups for publication, etc. She was a calming influence in those early years of graduate school.

The central preoccupation at IU psychology was learning theory, argued in seminar after seminar, up and down the halls, and over many, many beers. At this time, psychology was on the threshold of becoming a science, and questions were answered by experiments. Many pigeons and some rats labored in these endeavors. Bill, an apostate operant psychologist, labored on his aberrant statistical learning theory much to Skinner’s discomfiture and that of the experimental graduate students, who were now required to complete a math minor. Bill would listen silently as Norm Guttman (a pure by-the-book operant devotee) and I argued loudly and frequently about learning theory, occasionally interjecting to correct our errant ways. It was an exciting time.

Skinner, after many years of denigrating Harvard and the “Eastern Establishment,” turned tail and accepted the offer when it came, leaving behind many unhappy IU faculty and students. When asked why, he said that he “wanted to train the future leaders of the nation in behaviorism.” Instead, he trained a cohort of brilliant graduate students. When Verplanck followed Skinner to Harvard — an opportunity that Estes had rejected — Bill took over as chair of my doctoral committee, for which I am eternally grateful. It cost him and Kay many long hours of editing my thesis. I got my PhD with Bill in January 1951 and was probably one of his early PhDs. When I was elected to the Society of Experimental Psychologists at age 77, Bill sent a congratulatory e-mail: “About time.”

Although Bill eventually left IU to grace many famous institutions during his brilliant career, he told me that he and Kay were never happier than during their years at IU, where they retired. During the 2006 SEP meeting at IU, Bill took me on a tour of the campus to show me how much IU had changed since the early days. He was clearly at home.

Bill was a gentle genius, a renaissance scholar, inspirational and compassionate, and a faithful friend.

Alice F. Healy

University of Colorado, Boulder

I am devastated by the loss of Bill and find it very difficult to write about him. As my mentor, he had a huge impact on my work and my career. Here is an anecdote that I included at the end of my chapter in one of the two 1992 Festschrift volumes honoring Bill that I edited with Stephen Kosslyn and Richard Shiffrin:

A number of years ago, I had a discussion with a group of scientists about the relationship we had with our dissertation advisors. The general consensus seemed to be that the others were initially awed by their advisors but, as time progressed, the gap between their advisor’s knowledge and their own markedly decreased. I explained that my experience was quite different: Although I perceived the same initial gap, for me that gap seemed to grow with time as my appreciation for my advisor’s wisdom steadily increased. Another psychologist in the group responded, “That’s no surprise, Alice; your advisor was Bill Estes.”

An anecdote of a different type concerning Bill:

When I was a young faculty member at Yale, I was invited to serve on an NIMH study section. That seemed like daunting assignment to me at the time. I asked Bill whether he thought I should accept the invitation, and he told me that he had never turned down an invitation for professional service himself. That statement might seem hard to believe. But here is an excerpt from a 2000 encyclopedia entry I wrote about Bill (In A. Kazdin’sEncyclopedia of Psychology), which summarizes Bill’s remarkable service to the field (beyond his role as editor):

“Estes made immense contributions as a leader of many professional organizations in the field. He was one of the founders of the Psychonomic Society and was chair of the governing board in 1972, the year when the society’s journals were started. He was also chair of the organizing group of the Society for Mathematical Psychology and was chair of the society in 1984. Estes helped shape national science policy in his roles as member and chair of numerous committees and commissions of the National Research Council and grant panels of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the National Science Foundation.”

And that is just the tip of the iceberg.

Healy, A. F. (1992). William K. Estes.American Psychologist,47, 855-857.

Healy, A. F. (2000). Estes, William K. In A. Kazdin (Ed.),Encyclopedia of psychology(Vol. 3, pp. 237-238). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press.

Michael S. Gazzaniga

University of California, Santa Barbara

I met Bill only once, back in the heyday of split-brain research. Not everyone was excited by these findings. While riding up in the elevator at Rockefeller University, George Miller introduced me to the great American psychologist William Estes and said, “You know Mike, he is the guy that discovered the split-brain phenomenon in humans?” and Estes responded, “Great, now we have two systems we don’t understand!”

It was a sobering moment!

Douglas L. Medin

Northwestern University

One way to remember Bill is through stories. When I finished graduate school, I became an NIH postdoc with Bill at Rockefeller University. Mathematical psychology was new for me, and I had to work hard. Bill was an excellent role model in that regard. Finally, midway through the fall, I decided to take an evening off and attend a string quartet performance. To my considerable relief, Bill and Kay were also there. I was just thinking that even the stars in the field take time off, when I glanced down to where they were sitting and saw Bill pull out a small piece of paper and a pen and start writing. That ended the concert for me.

Soon after I came to Rockefeller University, Michael Cole and his lab group, fresh from doing cultural work in Liberia, joined the faculty, and he had his offices on the same floor of the Tower building as mine. By this time, I was enchanted with the elegance of mathematical models, including the ability of these models to account for some of my dissertation data. I thought Bill might be allergic to the kind of research that Mike was doing, and I once had the temerity to ask about what he thought of it. After the usual Estes pause, he proceeded to patiently explain to me that research areas often develop in different ways depending on the challenges they face, and that mathematical models only come into play at particular points of opportunity. Bill was a big fan of Mike’s research. Lesson learned.

Bill also taught me about the importance of failure. He once told me about how his first grant proposal in visual information was turned down because reviewers thought he should stick to his work on learning, and it wasn’t until after he had published twoProceedings of the National Academy of Sciencespapers on visual detection that he was able to get support. He went on to say that his grant proposal (actually the one that led me to postdoc with him) on reinforcement was also turned down, and he was able to get funding only after he published new theoretical papers on rewards as information (despite Estes and Skinner, 1941). He probably inspired Michael Jordan’s video on failure.

During that first year at Rockefeller University (when Bill had Don Robbins, Liz Bjork and me as postdocs, and George Wolford and Gordon Allen as graduate students), we all worked hard, but it was very difficult to tell what Bill thought of our performance. Finally, toward the end of the year, I got up my courage, went to Bill’s office, sat down with him and asked “How am I doing?” After a pause about three times the normal Estes length, during which Bill stared out the window and did a bit of the Bill Estes whistle, he finally turned to me and said, “Well, how do you think you’ve been doing?” I later learned that if you wanted to know what Bill thought of you, you could just ask Kay (“Bill thinks the world of you”), though she no doubt embellished a little (or maybe Bill thought the world of everyone).

But whether he showed it or not, Bill cared. Just one more note on this theme. Bill edited the Erlbaum six volume series, theHandbook of Learning and Cognitive Processes, which came out in the mid 1970s. Bill asked me to read and comment on a fair number of drafts of the contributed chapters, but I never saw the letters that went back to the authors and Bill never gave me feedback on whether my comments and suggestions were useful or off base. He did give me a copy of the volumes as they came out, and one day I noticed inside the cover of Volume 2 a handwritten note that said: “For Doug — No.1 Consultant. Bill

I miss him.

William H. Batchelder

University of California, Irvine

My story concerns probability learning. Most of us in the early 1960s were analyzing and comparing linear operator and stimulus sampling theory models for the two-light guessing experiment, known as probability learning. Under various sequential reinforcement rules, we would derive things like the conditional probability a participant would make an A(1) response on Trialngiven various short past sequences of responses and reinforcements. These derivations could be rough, and I remember working through the night to get them straight. About 15 years ago, Bill came to the University of California, Irvine, and gave a colloquium on learning models. He was comparing a set of five or so learning models on a complex set of data. One was based on a Hebbian rule, and there were variations on that. One of them, I can’t remember which, was fitting the learning curve best. I raised my hand and asked Bill why he didn’t try to compare the models on their predictions of conditional probabilities like we used to do for probability learning. His response was something like, “I can’t believe all the time I wasted trying to differentiate models on those sorts of statistics.” It took me quite a while to recover from that.

Gordon Bower

Stanford University

The passing of Bill Estes closes out a significant chapter for all of psychology and for me in a personal way. I have been very saddened, as I’ve followed the steady decline of Kay and Bill in the reports from their son, George, and their frequent visitor, Mark Gluck. Yet, Bill’s death also resurrects many happy memories for those of us who are thankful for having known him.

William (Bill) K. Estes and Katherine (Kay) W. Estes

Bill and I shared a long history of some 54 years. He became a mentor for me in the early days of my career. I first met Bill when I was a second-year graduate student at Yale and was invited to the 1957 summer Institute on Mathematical Learning Theory. That Institute was sponsored by the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) at Stanford and led by Bill, Pat Suppes, and Bob Bush. During that 6-week Institute, Bill and I formed a solid intellectual bond. Like many others, I was inspired by his insightful ideas. He encouraged me to write up my ideas as two chapters in the conference volume,Studies in Mathematical Learning Theory(Bush & Estes, 1959). We kept up a lively correspondence as I moved from Yale graduate school to Stanford in 1959 and he moved from Indiana to Stanford in 1961. Perhaps a basis for our early connection is that Bill and I both had roots in animal conditioning. Also, I was diligently recasting Hullian learning theory (dominant at Yale at that time) into the language of stimulus sampling theory (SST). Although that common interest established for us a satisfying linkage of SST to traditional work in animal conditioning, it did not yield the experimental work in human learning carried out later by Bill and then me.

Bill’s time at Stanford coincided with the 1960s growth of our mathematical psychology program led by Bill, Pat Suppes, Dick Atkinson, and me. That program attracted a large influx of bright young students, many of whom have become renowned contributors to our field. For all of us, Bill was our master teacher, lodestar, guru, and leader. As he was leaving Stanford for Rockefeller, the math psych program was being transformed into general cognitive psychology. Bill and I kept in touch, and he continued to inspire me from a distance. I expressed my appreciation and admiration of him in a chapter,Estes’ Stimulus Sampling Theory, in the 5th edition ofTheories of Learning (Bower & Hilgard, 1981). In 1994, I wrote a retrospective appreciation of Bill’s seminalPsych Review(1950) paper that had launched mathematical learning theory. We also spoke at and contributed chapters to each other’sFestschrifts:Bill’s at Harvard in 1992,mine at Stanford in 2005 when Bill was 86 years old! Throughout the years I had many opportunities to tell Bill and Kay how very important he was in my life and career and how central he was to the significant advances in modern psychology.

His amazing persistence and dedication to psychological science and his willingness to share and give of himself so freely were always powerful inspirations. I owe him a lifetime of loving gratitude.

Richard M. Shiffrin

Indiana University

I have found myself unable to write about both Bill and Kay in these last several months because I have so many memories and so many stories, I did not know where to start. Perhaps with my days at Stanford in the 1960s? My two sabbaticals/leaves with Bill at Rockefeller in the 1970s? The “Estes Family Dinners” at Psychonomics? Harvard’s remarkable mistreatment of Bill (and the William James house)? Bill’s final academic stop at Indiana, where he joined and was an active (for Bill) participant in my lab meetings every week? His sage advice and insistence on scientific quality at our faculty meetings? Our relations as neighbors in Bloomington, with houses 100 yards apart?

I’ll contribute two stories, albeit of a somewhat embarrassing nature:

First, the letter accepting me to Stanford University graduate school was signed by someone I had not heard of, someone named Estes. Never having been west of New Jersey, and still unsure whether to pursue psychology, law, or mathematics, I wrote back to this Estes person with a series of (inane) questions that had nothing to do with psychology or the graduate program. Instead, they were questions about trivial aspects of living in the Stanford area. One of many (idiotic) questions mentioned my worry about local parking spaces and the charges if I drove my car west. It took some time for Bill to respond, but the letter that eventually came was succinct and consisted of one line: “There is a good chance you will find parking.” Perhaps my letter prompted Estes to send me to Bower my first year…

Second, we have heard much about Bill’s excellent sense of humor. But this quality did not appear in such overt manifestations as smiling and laughing, a fact that had unforeseen consequences. When we held the fest for Bill at Psychonomics, I had trouble designing my talk. Knowing that Bill tended to be embarrassed by long speeches of praise, I decided to give a humorous talk, making light fun of his long years of research (this was, just barely, possible). When it was my turn to speak, I talked seriously before the silliness began. For just a moment, a few smiles started to emerge, but then all heads swiveled to look at Bill. He was not laughing. All the smiles stopped, and all the gazes turned back to me. No one would laugh if Bill didn’t, and he didn’t. Having no choice, I gave the prepared talk. In principle, the speech was quite funny, but in practice I learned firsthand the meaning of “dying on stage.” Later, Bill told me that he found the talk amusing (perhaps he was trying to console me?), but I am reasonably certain he would have enjoyed it more had the audience shown any overt signs that they also saw the humor.

Bill was a remarkable man and remarkable scientist. He saw more deeply into most subjects than anyone I knew. He had a tendency to think before he spoke, a style that seems to have gone out of vogue. He was actively engaged with research well into his 80s, and made insightful contributions to the research of postdoctoral visitors and graduate students in my lab right up to the days when ill health forced him and Kay to move east. It was often “funny” to be discussing research by some lab member, and then move on to another project, only to have Bill sit up straighter, clear his throat, and make some deep comment about the project we had left behind. I had the pleasure of watching this style of interaction from the 1960s to the 21st century.

He had a life and career worth celebrating.

Robert A. Bjork

University of California, Los Angeles

I feel that I could go on and on about this great man. We have lost a towering figure in our field, however slight of stature he may have been physically, and many of us have lost someone who managed to be, all at the same time, a mentor, colleague, and friend.

I’d like to share two stories:

The first involves my wife, Elizabeth Bjork, who joined Este’s Rockefeller lab in 1968 as a Research Associate. Bill was still in the process of setting up the lab, and Elizabeth (then Elizabeth Ligon) joined a group that included Doug Medin, George Wolford, and Don Robbins, plus Alice Healy and Steve Reder, who were beginning graduate students. We had warned Elizabeth before she left Michigan about Bill’s long pauses and how awkward those pauses could feel when interacting with him. What we heard back from Elizabeth, though, was a different story — about how, for example, Bill would drop by her office, put his feet up on the desk, and chat about what was on Broadway, where to get good ethnic foods, and so forth.

We were of course surprised by this apparent change, but the truth is that the early Rockefeller period seemed to be an unusually happy and relaxed period for Bill. In addition to having animated research discussions, the lab, as a group, including Bill, got caught up in matters such as whether Mark Spitz would win six gold medals in swimming in the 1968 Olympics, whether the Mets would win the 1969 World Series, and, especially, the 1969 U.S. Chess Championship, played in New York.

The second story is from the Ventura Hall era at Stanford. For a whole week the staff in Ventura Hall had put up big signs and banners announcing that “Friday is WKE Day,” meaning that we would celebrate Bill’s birthday that Friday. Bill never gave any sign of noticing all this advertising, and I remember worrying that the event was going to be very awkward. When we did finally gather and sing “happy birthday” to Bill as he came into the room, he looked around at everybody and, when the singing stopped, said, “What a surprise!” He then went on to be gracious, funny, and even loquacious. Only one of the many times Bill confounded our expectations.

Edward Smith

Columbia University

Bill Estes meant a great deal to me. Though I was already an assistant professor when I met him, he was a true mentor, as important to me as my graduate-school advisors. He had a deep intellect and was unusually kind to younger people in the field. I spent a sabbatical year with him at Rockefeller in 1976 and 1977, and it was one of the best years of my professional life. He was tremendously supportive in every way, and a great help to me and Doug Medin (then a postdoc) when we were writing a book together, which we dedicated to Bill. During that year, one of the of things that amazed me about Bill was that he left his office door open all the time, and if you wanted to talk to Bill you just knocked on the door and he would drop what he was doing and talk to you. I’ve never seen anything like it before or since. I last saw Bill about a year ago in New Jersey at what was to be Kay’s last birthday party. It still felt good to be in his presence.

Patrick Suppes

Stanford University

I first met Bill Estes in 1955, when we both were fellows at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, then as now, located at Stanford, but not part of Stanford until recently. I came to the Center with my only background in psychology being some earlier work in the measurement of subjective probability and utility. But in September of 1955, not long after our arrival, Bill and I began talking about his work in learning theory. At first it was mainly a matter of my listening to what he had to say. Pretty soon, I began thinking about what he had to say in terms of a formal axiomatic foundation, because I had already published some papers on the axiomatic foundations of classical mechanics and had been thinking of myself as mainly a philosopher of physics.

A photo of Estes (fourth from left in the first row) with other Members of the Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences at Stanford in 1967. First row: Lester Hyman, Richard Atkinson, Ed Crothers, William Estes, Gordon Bower, Harley Bernbach Second row: Unknown, Bill Mahler, Richard Shiffrin, Steve Link, Elizabeth Loftus, George Wolford Third row: Gordon Allen, David Tieman, John Holmgren, Bill Thompson, David Rumelhart Fourth row: Ken Wexler, Rich Freund, John Brelsford, Leo Keller Fifth row: Mike Clark, David Wessel, Peter Shaw, Don Horst, Dewey Rundus. Members not pictured include Pat Suppes, Guy Groen, Bob Bjork, Dave Wessel, Gary Olson, Bill Batchelder, Hal Taylor, Joe Young and Jim Townsend.

It ended up being a wonderful year. Bill and I worked together almost every day. We did not finish a single paper, but we started two large pieces of work, which were written up as technical reports by 1959. The first was on the foundations of linear models, published in the well-known volume on studies in mathematical learning theory edited by Bob Bush and Bill. The second remained as a very long unpublished technical report entitled “Foundations of Statistical Learning Theory II: The Stimulus Sampling Model” (Technical Report 26, Institute for Mathematical Studies in the Social Sciences, Stanford University). I enormously enjoyed writing this long report with Bill, and I still remember the intense concentration we put into finishing it in August of 1959. In 1974, we published a reduced version in a book edited by Dave Krantz, Dick Atkinson, Duncan Luce, and myself.

In my long academic career I have had many collaborators, but the work with Bill in the late 1950s is still vivid in my memory, perhaps because I was learning so much from him while we were working together on something new. Bill and I did not collaborate on any further work, even though we had many conversations about research that we would like to do but never quite managed to start. We remained close friends, and I got much encouragement from Bill to continue my work in psychology, especially now that he had trained me so well.

One further remark about Bill. A lot of smart people have done superb work in learning theory and other parts of psychology related to it since 1950, but there is something really special about Bill’s work. His 1950 article inPsychological Reviewentitled “Towards a Statistical Theory of Learning” marks a historical turning point. Prior to 1950, there were many able and intelligent psychologists who wrote about learning. This list includes Guthrie, Hilgard, Hall, Skinner, Thorndike, Thurstone, Tolman, and Watson. Bill’s seminal 1950 contribution was more radical than it seemed. Why was this so? For the first time an approach to learning theory had a framework of concepts that permitted serious mathematical development and, thereby, a variety of quantitative predictions that could be thoroughly tested from a statistical standpoint. This was a revolution, and it should be understood in many ways as the greatest intellectual contribution Bill made to the history of psychology. This is not the place for me to spell out this argument in more detail. Still it is important to note this point for the many younger scientists that Bill influenced so much, but perhaps they are too young to be very familiar with the revolution of the 1950s that Bill started. Here is the memorable first sentence of his famous paper:

“Improved experimental techniques for the study of conditioning and simple discrimination learning enable the present-day investigator to obtain data which are sufficiently orderly and reproducible to support exact quantitative predictions of behavior.”www.psychspace.com心理学空间网