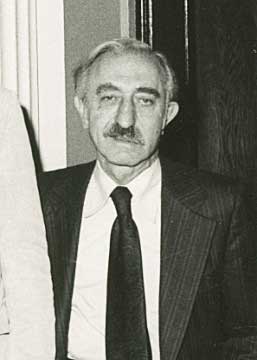

Dr. Milton Rokeach, 1979

Introduction

The psychology of dogmatism is as relevant today as when Dr. Milton Rokeach began his pioneering work into this enduring topic. The ideas contained within this important paper informed the development of the Rokeach Dogmatism Scale and stimulated research into the psychology of human belief systems and dogmatism as a personality trait.

The Article in Full

In this paper we will attempt to provide the theoretical groundwork for a research project on the phenomenon of dogmatism in various spheres of human activity—political, religious, and scientific. Our main purpose is to present a detailed theoretical statement of the construct of dogmatism which is guiding the research. More specifically, we will define the phenomenon of dogmatism by representing it as a hypothetical cognitive state which mediates objective reality within the person, describe the properties of its organization, and present a number of postulates regarding the relation between dogmatism and other variables. On the basis of part of such a formulation we have thus far developed a preliminary scale for measuring individual differences in dogmatism and several testable hypotheses relevant to our conceptual definition (to be reported subsequently).

A second purpose stems from the fact that our construct of dogmatism involves the convergence of three highly interrelated sets of variables: closed cognitive systems, authoritarianism, and intolerance. By virtue of this convergence it will be possible to examine certain assumptions underlying previous research on authoritarianism and intolerance with the aim of achieving a possibly broader conceptualization of these phenomena.

It is not within the scope of this paper to inquire into the social or personal conditions which give rise to dogmatism. This is considered to be an independent theoretical problem. Having defined the problem of dogmatism and its representation at the cognitive level—the main purpose of this paper—one can then seek explanations according to one's theoretical orientation.

A basic assumption guiding the present formulation is that despite differences in ideological content, analysis will reveal certain uniformities in the structure, the function, and, to some extent, even the content of dogmatism. Accordingly, attention will be directed to both political and religious dogmatism and, within each area, to diverse and even opposed dogmatic orientations. In the religious sphere, for example, one can observe expressions of dogmatic Catholicism and dogmatic anti-Catholicism, dogmatic orthodox Judaism and dogmatic antiorthodox Judaism, dogmatic theism and dogmatic atheism. In the political sphere one can observe expressions of dogmatic conservatism and dogmatic liberalism, dogmatic Marxism and dogmatic anti-Marxism.

The problem of dogmatism, however, is not necessarily restricted to the political and religious spheres. It can be observed in other realms of intellectual and cultural activity—in philosophy, the humanities, and the social sciences. To take some examples from psychology, it is possible to observe expressions of dogmatic Freudianism and dogmatic anti-Freudianism, dogmatic learning theory and dogmatic antilearning theory, dogmatic gestalt theory and dogmatic antigestalt theory, and so forth.

Dogmatism, furthermore, need not necessarily involve adherence to this or that group-shared, institutionalized system of beliefs. It is conceivable that a person, especially one in academic circles, can be dogmatic in his own idiosyncratic way, evolving a unique rather than institutionalized integration of ideas and beliefs about reality. The present formulation will attempt to address itself to noninstitutional as well as institutional aspects of dogmatism.

GENERAL SETTING FOR A COGNITIVE REPRESENTATION OF DOGMATISM

To conceptualize dogmatism adequately at the cognitive level it is first necessary to employ a set of conceptual tools in terms of which all cognitive systems, varying in degree of dogmatism, may be represented.

Organization into Belief and Disbelief Systems

Objective reality can be assumed as being represented within a person by certain beliefs or expectations which to one degree or another are accepted as true, and other beliefs or expectations accepted as false. For the sake of analysis this can be formalized by conceiving of all cognitive systems as being organized into two interdependent parts: a belief system and a disbelief system. This belief-disbelief system can further be conceived as varying in terms of its structure and content as follows:

Structure

The total structure of a belief-disbelief system can be described as varying along a continuum from open to closed. This continuum, in turn, may be conceived as a joint function of: (a) The degree of interdependence among the parts within the belief system, within the disbelief system, and between belief and disbelief systems (6, 7, 9, 12). (b) The degree of interdependence between central and peripheral regions of the belief-disbelief system (9). (c) The organization of the belief-disbelief system along the time perspective dimension (2, 3, 4, 8).

Content

One can further describe all belief-disbelief systems in terms of the formal content of centrally located beliefs, especially those having to do with beliefs about authority and people in general.

A COGNITIVE REPRESENTATION OF DOGMATISM

In line with the above considerations we will now define dogmatism as (a) a relatively closed cognitive organization of beliefs and disbeliefs about reality, (b) organized around a central set of beliefs about absolute authority which, in turn, (c) provides a framework for patterns of intolerance and qualified tolerance toward others. A cognitive organization is considered to be closed to the extent that there is (a) isolation of parts within the belief system and between belief and disbelief systems, (b) a discrepancy in the degree of differentiation between belief and disbelief systems, (c) dedifferentiation within the disbelief system, (d) a high degree of interdependence between central and peripheral beliefs, (e) a low degree of interdependence among peripheral beliefs, and (f) a narrowing of the time perspective.

More specifically, in the relatively closed belief-disbelief system there is assumed to be a relation of relative isolation among the various parts of the belief system and between belief and disbelief systems. The latter, in turn, is composed of a series of disbelief subsystems, each arranged along a gradient of similarity to the belief system, the most similar disbelief subsystems being represented as regions most adjacent to the belief system. Each of these disbelief subsystems is conceived, to the extent that it is part of a closed system, as being relatively less differentiated than the belief system and, the farther away their positions from the belief system, as increasingly dedifferentiated with respect to each other.

Belief-disbelief systems can also be represented along a central-peripheral dimension. The more closed the system the more the central part corresponds to absolute beliefs in or about authority, and the more the peripheral part corresponds to beliefs and disbeliefs perceived to emanate from such authority.

With respect to the time perspective dimension, increasingly closed systems can be conceived as being organized in a relatively future-oriented or past-oriented direction rather than in terms of a more balanced orientation of past, present, and future.

With regard to the content of dogmatism, while the specific content of both central and peripheral parts may vary from one particular ideological system to another, it is possible to specify that in general the formal content of the central part of the system, to the extent it is closed, has to do with absolute beliefs in and about positive and negative authority, either external or internal, and related beliefs representing attempts on the part of such authority to perpetuate itself. Furthermore, the central part can be conceived to provide a framework for the organization of other beliefs representing patterns of rejection and qualified acceptance of people in general according to their patterns of agreement and disagreement with the belief-disbelief system.

DOGMATISM DISTINGUISHED FROM RIGIDITY

Before going on to elaborate further on our conceptual definition of dogmatism, it may be illuminating first to distinguish the construct of dogmatism in a general way from that of rigidity. Both dogmatism and rigidity refer to forms of resistance to change, but dogmatism is conceived to represent a relatively more intellectualized and abstract form than rigidity. Whereas dogmatism refers to total cognitive organizations of ideas and beliefs into relatively closed ideological systems, rigidity, when genotypically conceived, refers solely to the degree of isolation between regions (7, 12) or to a "property of a functional boundary which prevents communication between neighboring regions" (6, p. 157); when phenotypically conceived, rigidity is denned in terms of the way a person or animal attacks, solves, or learns specific tasks and problems (11). Thus, dogmatism is seen as a higher order and more complexly organized form of resistance to change. While dogmatism may well be hypothesized to lead to rigidity in solving specific problems, the converse is not necessarily the case. Rats, the feebleminded, and the brain-injured, for example, can be characterized as rigid (also compulsive, fixated, perseverative, inflexible) but hardly as dogmatic.

Furthermore, whereas rigidity refers to person-to-thing or animal-to-thing relationships, dogmatism is manifested almost necessarily in situations involving person-to-person communication. Thus, we speak of a person as tying his shoelaces or solving an arithmetic problem rigidly, but of a professor, a politician, an orator, a theoretician, or an art critic as expressing himself to others dogmatically.

A final differentiation, closely related to the preceding, is that dogmatism has a further reference to the authoritarian and intolerant manner in which ideas and beliefs are communicated to others. Thus, the range of behavior considered under the rubric of dogmatism is considerably broader than rigidity and at the same time of possibly more intrinsic interest to the sociologist, the political scientist, and the historian, as well as the psychologist.

POSTULATES INVOLVING THE COGNITIVE STRUCTURE OF DOGMATISM

To the extent that the belief-disbelief system is closed, it is subjected to continual stresses and strains from objective and social reality. Reality can be coerced into congruence with the belief-disbelief system by virtue of the arrangement of parts within the belief-disbelief systems, within and between the central and peripheral regions thereof, and by virtue of its organization along the time perspective dimension.

A. Isolation within and between Belief and Disbelief Systems

The greater the dogmatism the greater are the assumed degree of isolation or independence between the belief and disbelief systems and the assumed degree of isolation among the various parts of the belief system. On the basis of these considerations we introduce the following postulates:

1. Accentuation of differences between belief and disbelief systems.

The greater the dogmatism the more will the belief system be perceived as different in content or aim from the disbelief system (e.g., Catholicism and Protestantism; the United States and the USSR; fascism and communism; psychoanalysis and behaviorism).

2. The perception of irrelevance.

The greater the dogmatism the more will ideological arguments pointing to similarities between belief and disbelief systems be perceived as irrelevant.

3. Denial.

The greater the dogmatism the greater the denial of events contradicting or threatening one's belief system (e.g., on grounds of "face absurdity," that the true facts are not accessible, that the only available sources of information are biased because they are seen to emanate from the disbelief system, etc.).

4. Coexistence of contradictions within the belief system.

In line with the assumption that in increasingly closed cognitive organizations there is relatively more isolation among subparts of the belief system, as well as between belief and disbelief systems, it is postulated that the degree of adherence to contradictory beliefs will vary directly with the degree of dogmatism. Some examples of contradictory beliefs are an abhorrence of violence together with the belief that it is justifiable under certain conditions; expressions of faith in the intelligence of the common man and at the same time the belief that the masses are stupid; a belief in democracy and along with this the belief that our country can best be run by an intellectual elite; a belief in freedom for all but at the same time the belief that freedom for certain groups should be restricted; a belief that science makes no value judgments about "good" and "bad" but also that scientific criteria are available for distinguishing "good" theory from "bad" theory, and "good" experiment from "bad" experiment (13).

B. The Disbelief Gradient

We have already indicated that in relatively closed systems there is relative isolation between belief and disbelief systems. However, the various disbelief subsystems cannot all be assumed to be equally isolated from the belief system. Rather, degree of isolation can further be conceived as varying with the degree of perceived similarity of the various disbelief subsystems to the belief system. Those disbelief subsystems most similar to the belief system can be represented as regions most adjacent to the belief region and, hence, in relatively greater communication or interaction with the belief system than less similar disbelief subsystems.

1. Strength of rejection of various disbelief subsystems.

The greater the dogmatism the more will the disbelief subsystem most similar to the belief system (factional or "renegade" subsystems) be perceived as threatening the validity of the belief system and hence the greater the tendency to exert effort designed to reject this subsystem and the adherents thereof. For example, with an increase in dogmatism there will be an increasingly militant rejection of Protestantism by the Catholic, of reformed Judaism by the more conservative Jew, of Trotskyism and Titoism by the Communist, and vice versa. In the academic realm, too, the greater the dogmatism the more antagonism there will be among representatives of divergent views within a single discipline as compared with related disciplines.

2. Willingness to compromise.

Even though a person or group may reject a disbelief system it is often necessary, for the sake of achieving political or religious aims, to form working alliances with other individuals or groups. It is here postulated that such compromising varies inversely with dogmatism: the greater the dogmatism the less compromise there will be with adherents to the disbelief subsystem closest to the belief system.

C. Relative Degrees of Differentiation of Belief and Disbelief Systems

In our cognitive representation of dogmatism we have assumed that the greater the dogmatism the more differentiated the belief system will be as compared with the disbelief system. Moreover, various disbelief subsystems have been assumed to become relatively more dedifferentiated with respect to each other the farther away their positions from the belief system.

The following postulates are based upon these considerations:

1. Relative amount of knowledge possessed.

The greater the dogmatism the greater the discrepancy between degree of knowledge of facts, events, ideas, and interpretations stemming from the belief system and any one of the disbelief subsystems. Thus, for example, with an increase in dogmatism there will be an increasing discrepancy in the Freudian's knowledge of classical psychoanalysis as compared with Adlerian psychology or learning theory.

2. Juxtaposition of beliefs and disbeliefs.

Under special conditions, however, e.g., social or personal conditions which lead to disillusionment with the belief system and thence to conversion wherein beliefs and disbeliefs become juxtaposed, it is conceivable that one of the disbelief subsystems will be more differentiated than the belief system. It is therefore postulated that as a function of the reversal of belief and disbelief systems, the greater the dogmatism the greater the discrepancy between degrees of differentiation of belief and disbelief systems in favor of the latter.

3. Dedifferentiation within the disbelief system.

The greater the dogmatism the more will two or more disbelief subsystems represented as positions relatively far away from the belief system along the disbelief gradient be perceived as "the same" (e.g., that communism and socialism are the same, that the Democrats and Republicans are both run by Wall Street, etc.).

D. Relation between Central and Peripheral Parts

We have assumed further that, to the extent we are dealing with closed systems, the central part corresponds to beliefs in and about absolute authority and the peripheral part to beliefs and disbeliefs perceived to emanate from such authority. Thus, the more closed the system the greater the assumed degree of communication between central and peripheral beliefs and, at the same time, the less the assumed degree of communication among the various peripheral beliefs. From these considerations it follows also that any given change in the peripheral part represents an isolated change in cognitive content without concomitant changes either in cognitive structure or in over-all ideological content.

It is this interrelation between central and peripheral parts which gives the relatively closed system its integrated and systematic character. Specific peripheral beliefs and disbeliefs are organized together not so much by intrinsic logical connections as by virtue of their perceived origination with positive and negative authority, respectively. Whatever characterizes the authority's ideology, as represented by the central part, will be mirrored "gratuitously" in the closed system.

If the authority is logical, the closed system will appear logical; if the authority is illogical, the closed system will appear illogical. The more closed the system the more will it reflect in toto the authority's own system with its logic or illogic, its manifest intellectualism or anti-intellectualism, and so forth.

1. "Party-line" changes.

It is commonly observed that relatively dogmatic views on specific issues are stubbornly resistant to change by logical argument or objective evidence. One possible reason for this becomes apparent in the light of the preceding considerations. The greater the dogmatism the more will there be a change in a given peripheral belief (e.g., about birth control) if it is preceded by a perceived corresponding change by the authority (e.g., the Catholic Church). Moreover, the greater the dogmatism the less will any given change in a peripheral belief effect changes in other peripheral beliefs (e.g., about divorce, federal aid to education, etc.).

2. Assimilation.

Further considerations regarding the relation between central and peripheral parts lead also to the following postulate: The greater the dogmatism the greater the assimilation of facts or events at variance with either the belief or disbelief system by altering or reinterpreting them such that they will no longer be perceived as contradictory.

3. Narrowing.

Assuming, as we have, that the central region is crucial in determining what aspects of reality will be represented within the peripheral region, it follows that it will also be crucial in determining what aspects of reality will not be represented (12). The greater the dogmatism the more the avoidance of contact with stimuli—people, events, books, etc.—which threaten the validity of the belief system or which proselyte for competing disbelief systems.

Cognitive narrowing may be manifested at both institutional and noninstitutional levels. At the institutional level, narrowing may be manifested by the publication of lists of taboo books, the removal and burning of dangerous books, the elimination of those regarded as ideological enemies, the omission of news reports in the mass media unfavorable to the belief system or favorable to the disbelief system, and the conscious and unconscious rewriting of history (10).

At the noninstitutional level, narrowing may become apparent from the systematic restriction of one's activities in order to avoid contact with people, books, ideas, social and political events, and other social stimuli which would weaken one's belief system or strengthen part of one's disbelief system. Relevant here are such things as exposing oneself only to one point of view in the press, selectively choosing one's friends and associates solely or primarily on the basis of compatibility of belief systems, selectively avoiding social contact with those adhering to different belief systems, and avoiding those who formerly believed as one does.

In academic circles cognitive narrowing over and above that demanded by present day specialization may be manifested by a selective association with one's colleagues and selective subscription, purchase, and reading of journals and books such that one's belief system becomes increasingly differentiated while one's disbelief system becomes increasingly dedifferentiated or "narrowed out."

E. Time Perspective

1. Attitude toward the present.

The greater the dogmatism the more will the present be perceived as relatively unimportant in its own right—as but a passageway to some future Utopia. Furthermore, with an increase in dogmatism there will be a concomitant increase in the perception of the present as unjust and as full of human suffering.

2. Belief in force.

Such a disaffected conception of the present can readily lead to the belief that a drastic revision of the present is necessary. Thus, we are also led to the following postulate: The greater the dogmatism the greater the condonement of force.

3. Knowing the future.

Another aspect of time perspective has to do with one's understanding of the future. With an increase in dogmatism there will be the following variations: an increasing confidence in the accuracy of one's understanding of the future, a generally greater readiness to make predictions, and a decreasing confidence in the predictions of the future made by those adhering to disbelief systems.

POSTULATES INVOLVING THE COGNITIVE CONTENT OF DOGMATISM

We have already pointed out that while the specific content of beliefs and disbeliefs varies from one system to another, it is nevertheless possible to point to certain uniformities in the formal content of centrally located beliefs which, to the extent that they are part of a closed system, form the cognitive bases for authoritarianism and intolerance.

A. Authoritarianism

At the center of the belief-disbelief system, to the extent it is closed, is assumed a set of absolute beliefs about positive and negative authority and other closely related beliefs representing attempts by such authority to reinforce and perpetuate itself.

1. Positive and negative authority.

With an increase in dogmatism there will be not only increasing admiration or glorification of those perceived in positions of positive authority but also increasing fear, hatred, and vilification of those perceived in positions of authority opposed to positive authority.

2. The cause.

With an increase in dogmatism there will be an increasing strength of belief in a single cause and concomitantly a decreasing tendency to admit the legitimacy of other causes. Manifestations of strength of belief in a single cause might be making verbal references to "the cause," expressing oneself as "feeling sorry" for those who do not believe as one does, believing that one should not compromise with one's ideological enemies, perceiving compromise as synonymous with appeasement, believing that one must be constantly on guard against subversion from within or without, and believing that it is better to die fighting than to submit.

3. The elite.

With an increase in dogmatism there will be an increase in strength of belief in an elite (political, hereditary, religious, or intellectual).

B. Intolerance

Beliefs in positive and negative authority, the elite, and the cause all have to do with authority as such. Coordinated with such beliefs are others representing organizations of people in general according to the authorities they line up with. In this connection there may be conceived to emerge, with increasing dogmatism, increasingly polarized cognitive distinctions between the faithful and unfaithful, orthodoxy and heresy, loyalty and subversion, Americanism and un-Americanism, and friend and enemy. Those who disagree are to be rejected since they are enemies of God, country, man, the working class, science, or art. Those who agree are to be accepted but only as long as and on condition that they continue to do so. This sort of qualified tolerance is, to our mind, only another form of intolerance. That it can turn quickly into a frank intolerance is often seen in the especially harsh attitude taken toward the renegade from the cause.

It is in this way that the problem of acceptance and rejection of people can become linked not only with authoritarianism but also with the acceptance and rejection of ideas. Perhaps the most clear-cut single behavioral manifestation of this linkage is the employment of opinionated language in communicating beliefs and disbeliefs to others. Opinionation is a double-barrelled sort of variable which refers to verbal communications involving acceptance or rejection of beliefs in an absolute manner and, at the same time, acceptance or rejection of others according to whether they agree or disagree with one's beliefs.

1. Opinionated rejection.

This refers to verbal statements which imply absolute rejection of a belief and at the same time rejection of persons who accept it. The following examples illustrate this:

"Only a simple-minded fool would think that . . . ," "A person must be pretty stupid to think . . . ," "The idea that . . . is pure hogwash (or poppycock, nonsense, silly, preposterous, absurd, crazy, insane, ridiculous, piddling, etc.)."

The preceding considerations lead us to postulate that opinionated rejection will vary directly with dogmatism.

2. Opinionated acceptance.

This refers to an absolute acceptance of a belief and along with this a qualified acceptance of those who agree with it. Some examples are: "Any intelligent person knows that . . . ," "Plain common sense tells you that . . . ."

Opinionated acceptance will also vary directly with dogmatism.

SOME IMPLICATIONS FOR FURTHER THEORY AND RESEARCH ON AUTHORITARIANISM AND INTOLERANCE

Through the pioneering research of Adorno et al. (1) significant theoretical and empirical advances have been made recently in understanding the phenomena of authoritarianism and intolerance. Since our construct of dogmatism also involves a representation of these phenomena, it is proper to ask: To what extent is the present formulation of the problem of dogmatism consonant with the work on the authoritarian personality?

To be noted first is a historical fact. The research on the authoritarian personality was launched at a time when the problem of fascism and its attendant anti-Semitism and ethnocentrism was of overriding concern to both social scientist and layman. Given this social setting as a point of departure, it was almost inevitable that the general problem of authoritarianism would become more or less equated with the problems of adherence to fascist ideology and ethnic intolerance. Thus, the personality scale designed to tap underlying predispositions toward authoritarianism was called the F (for fascism) Scale and was found to correlate substantially with measures of ethnic intolerance.

It is widely recognized, however, that authoritarianism is also manifest among radicals, liberals, and middle-of-the-roaders as well as among conservatives and reactionaries. Furthermore, authoritarianism can be recognized as a problem in such areas as science, art, literature, and philosophy, where fascism and ethnocentrism are not necessarily the main issues or may even be totally absent as issues. As pointed out in this paper, dogmatism, which is assumed to involve both authoritarianism and intolerance, need not necessarily take the form of fascist authoritarianism or ethnic intolerance.

It is thus seen that the total range of phenomena which may properly be regarded as indicative of authoritarianism is considerably broader than that facet of authoritarianism studied so intensively by the authors of The Authoritarian Personality. On theoretical grounds, we are in accord with the view that authoritarianism has a greater affinity to leanings to ideologies which are antidemocratic in content. But it need not be conceived as uniquely connected with such ideologies. If a theory of authoritarianism is to be a general one, it should also be capable of addressing itself to the fact that to a great extent authoritarianism cuts across specific ideological orientations. As we have tried to suggest, dogmatic authoritarianism may well be observed within the context of any ideological orientation, and in areas of human endeavor relatively removed from the political or religious arena.

One way to test the validity of the above considerations is to demonstrate that scores on the F Scale are related substantially to measures of dogmatism independently of liberalism-conservatism, or of the kinds of attitudes held toward such groups as Jews and Negroes. The results of one study, already reported (14), show that dogmatism and authoritarianism correlate over .60 when ethnocentrism or political-economic conservatism is held constant. Corroborative findings from several studies will be presented in a more detailed future report.

Consider further the way the problem of intolerance has been conceived in social-psychological research (1, 5). Parallel to the more or less rough equating of authoritarianism with fascism, and perhaps for similar reasons, intolerance too can be said to have become more or less equated with one aspect of intolerance, namely, ethnic intolerance. Examination reveals that such concepts as intolerance, discrimination, bigotry, social distance, prejudice, race attitudes, and ethnocentrism are all defined operationally in much the same way—by determining how subjects feel or act toward Jews, Negroes, foreigners, and the like.

It is reasonable to assume that there are persons who, although they would validly score low on measures of ethnocentrism or similar scales presently in use, would nevertheless be characteristically intolerant of those whose belief-disbelief systems are at odds with their own.

It has already been suggested that while dogmatic authoritarianism may "attach" itself to any ideology, it is probably more closely related to those having antidemocratic content. A similar point may well be made in connection with dogmatic intolerance. Preliminary data already available suggest that measures of dogmatic intolerance (opinionation) and ethnic intolerance are, as expected, related to each other to a significant degree. At the same time they are also found to cut across each other in a relatively independent fashion. The preceding considerations point to other aspects of man's intolerance to man, in addition to ethnic intolerance, which deserve scientific attention. And, as we have tried to point out in discussing the problem of authoritarianism, here too we think there is a need for a more comprehensive conceptualization of the problem of intolerance.

SUMMARY

To provide a framework for empirical research we have attempted a conceptual representation of the phenomenon of dogmatism by describing in some detail the properties of its cognitive organization. Dogmatism has been defined as (a) a relatively closed cognitive system of beliefs and disbeliefs about reality, (b) organized around a central set of beliefs about absolute authority which, in turn, (c) provides a framework for patterns of intolerance and qualified tolerance toward others.

We have described this relatively closed cognitive organization in terms of the degree of interdependence among the various parts of the belief-disbelief system, its organization along a central-peripheral dimension, and its organization along a time perspective dimension. We have also described how relatively closed systems could be conceived as being organized around a central part, the formal content of which forms the cognitive bases for patterns of beliefs involving authoritarianism and intolerance.

On the basis of various aspects of this hypothetical model of a continuum ranging from the "closed mind" to the "open mind" we have advanced a series of postulates regarding the relation between dogmatism, conceived as a hypothetical construct having the status of an independent variable, and other variables.

Furthermore, from our theoretical formulation certain implications were drawn for present thinking and research on the problems of authoritarianism and intolerance. We suggested that selective factors may have operated in such a way that research on both authoritarianism and intolerance has become more or less reduced to and synonymous with but one form of authoritarianism, fascism, and with but one form of intolerance, ethnic intolerance. We suggested too that present thinking and research along these lines are in need of extension in the light of both theoretical considerations and findings which indicate that dogmatic authoritarianism and intolerance cut across in an independent fashion such variables as ethnocentrism, political-economic conservatism, and fascist authoritarianism.

REFERENCES

1. ADORNO, T W., FRENKEL-BRUNSWIK, ELSE, LEVINSON, D. J , & SANFORD, R. N. The authoritarian personality. New York" Harper, 1950

2. CROSSMAN, R The god that failed. New York- Harper, 1949

3. FRANK, L. K. Time perspectives. J. soc. Phil., 1939,

4, 293-312. 4. HOFFER, E. The true believer. New York: Harper, 1951.

5. JAHODA, MARIE, DEUTSCH, M., & COOK, S W. Research methods in social relations. New York: Dryden, 1951.

6. KOUNIN, J. The meaning of rigidity: a reply to Heinz Werner. Psychol. Rev., 1948, 55, 157-166.

7. KRECH, D. Notes toward a psychological theory. / Pers., 1949, 18, 66-87.

8. LEWIN, K Time perspective and morale. In G Watson (Ed.), Civilian morale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1942

9. LEWIN, K. Field theory in social science New York: Harper, 1951.

10 ORWELL, G 1984. New York: New American Library, 1951.

11. ROKEACH, M. Generalized mental rigidity as a factor in ethnocentrism. /. abnorm. soc Psychol, 1948, 43, 259-278

12. ROKEACH, M A method for studying individual differences in "narrow-mindedness." /. Pers., 1951, 20, 219-233. 13. ROKEACH, M. Toward the scientific evaluation of social attitudes and ideologies. J. Psychol., 1951, 31, 97-104. 14. ROKEACH, M. Dogmatism and opinionation on the left and on the right. Amer. Psychologist, 1952, 7, 310. (Abstr

www.psychspace.com心理学空间网