Surely one of the best ways to generate motivation in ourselves and others is by dangling rewards?

的确奖励是催生动力的最好的方法之一。

Yet psychologists have long known that rewards are overrated. The carrot, of carrot-and-stick fame, is not as effective as we've been led to believe. Rewards work under some circumstances but sometimes they backfire. Spectacularly.

然而很久以来心理学家认为奖励的作用被高估了。萝卜加大棒中的萝卜并没有我们相信的那么有效。奖励在一些情形下有用,而在一些情况下却会适得其反。

Here is a story about preschool children with much to teach all ages about the strange effects that rewards have on our motivation.

这里关于学龄前儿童的故事可以让所有人看到奖励对我们的动力的神奇的作用。

It's child's play

这是孩子的游戏。

Psychologists Mark R. Lepper and David Greene from Stanford and the University of Michigan were interested in testing what is known as the 'overjustification' hypothesis—about which, more later (Lepper et al., 1973).

来自斯坦福大学的心理学家马克·R·莱佩尔和密歇根大学的心理学家大卫·格林对过度合理化假设的测验感兴趣,关于这一点,更多信息在(Leeper et al., 1973)

Since parents so often use rewards as motivators for children they recruited fifty-one preschoolers aged between 3 and 4. All the children selected for the study were interested in drawing. It was crucial that they already liked drawing because Lepper and Greene wanted to see what effect rewards would have when children were already fond of the activity.

因为父母经常把奖励作为激励孩子的因素,他们招募了51个年龄在3到四岁的学龄前儿童。所有参与研究的儿童都对绘画感兴趣。这是很关键的,因为莱佩尔和格林想要观察奖励在孩子们喜欢的活动中起到什么样的作用。

The children were then randomly assigned to one of the following conditions:

随后孩子们被随机分配到下面的其中一种情境中:

Expected reward. In this condition children were told they would get a certificate with a gold seal and ribbon if they took part.

期望的奖励。在这种情境中,孩子们被告知,如果她们参与实验的话,就会得到一份带有金色印章和缎带的证书。

Surprise reward. In this condition children would receive the same reward as above but, crucially, weren't told about it until after the drawing activity was finished.

意外惊喜的奖励。在这种情境中,他们同样会得到上面那种情境下的奖励,不过关键一点是,他们是在绘画活动结束之后才被告知这一情况的。

No reward. Children in this condition expected no reward, and didn't receive one.

没有奖励。这一情境中的孩子没有期望的奖励,也不会得到意外的惊喜。

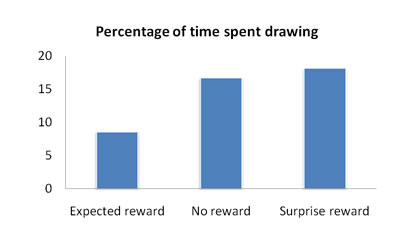

Each child was invited into a separate room to draw for 6 minutes then afterwards either given their reward or not depending on the condition. Then, over the next few days, the children were watched through one-way mirrors to see how much they would continue drawing of their own accord. The graph below shows the percentage of time they spent drawing by experimental condition:

每个孩子被带到一个单独的房间里作画6分钟,随后根据设定的情境给予或不给他们奖励。然而,随后的几天里,通过单向的玻璃镜观察孩子们是多么自愿地持续绘画。下面就是根据实验情境得来的他们作画时间的百分比图标:

As you can see the expected reward had decreased the amount of spontaneous interest the children took in drawing (and there was no statistically significant difference between the no reward and surprise reward group). So, those who had previously liked drawing were less motivated once they expected to be rewarded for the activity. In fact the expected reward reduced the amount of spontaneous drawing the children did by half. Not only this, but judges rated the pictures drawn by the children expecting a reward as less aesthetically pleasing.

就像你看到的那样,在有期望奖励的情境下的孩子们自发的绘画的兴趣已经下降了(而没有奖励或有意外奖励的组在统计数值上没有什么重大的区别)。所以,那些先前喜欢绘画的孩子们,在对他们的活动给予期望的奖励后,他们的动力反而减少了。事实上期望的奖励降低了一半的自发作画的兴趣。不仅如此,对有期望奖励的孩子们的相关的绘画的没有那么有美感。

Rewards reduce intrinsic motivation

奖励减少了内在的动力。

It's not only children who display this kind of reaction to rewards, though, subsequent studies have shown a similar effect in all sorts of different populations, many of them grown-ups. In one study smokers who were rewarded for their efforts to quit did better at first but after three months fared worse than those given no rewards and no feedback (Curry et al., 1990). Indeed those given rewards even lied more about the amount they were smoking.

这不仅是因为孩子们作画是因为有奖励,后来的研究也显示了在所有不同的人群中类似的作用,他们中的大多数是成年人。在一项研究中,给予尽力戒烟的人期望的奖励的话,他们在刚开始的时候做的很好,但三个月后他们比那些没有奖励的人的结果更糟糕(Curry et al., 1990).实际上,那些给予期望奖励的戒烟者更容易就他们吸烟的数量说谎。

Reviewing 128 studies on the effects of rewardsDeci et al. (1999, p. 658)concluded that:

回顾128项奖励的作用的研究 Deci et al.(1999.p.658),得出一下结论:

"tangible rewards tend to have a substantially negative effect on intrinsic motivation (...) Even when tangible rewards are offered as indicators of good performance, they typically decrease intrinsic motivation for interesting activities."

切实的奖励对内在的动力有本质上的负面的作用(……),即使切实的奖励是作为对表现优秀的一种指示,他们也会减少对感兴趣的活动的内在的动力。

Rewards have even been found to make people less creative andworse at problem-solving.

研究甚至还发现奖励会降低人的创造性和解决问题的能力。

Overjustification

过度合理化

So, what's going on? The key to understanding these behaviours lies in the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. When we do something for its own sake, because we enjoy it or because it fills some deep-seated desire, we are intrinsically motivated. On the other hand when we do something because we receive some reward, like a certificate or money, this is extrinsic motivation.

所以,到底发生了什么?要理解这些行为的关键是区分内在动力和外在的动力。当我们为了事物本身的利益去做某事的时候,是因为我们喜爱他或者它满足了一些我们深层次的需要,我们是内在的被驱动了。另一方面当我们为了得到奖励而去做某事的时候,比如证书或者金钱,就是外在的动机。

The children were chosen in the first instance because they already liked drawing and they were already intrinsically motivated to draw. It was pleasurable, they were good at it and they got something out of it that fed their souls. Then some of them got a reward for drawing and their motivation changed.

第一中情境下的孩子们,因为他们已经喜爱作画了,所以他们已经被内在的动力驱动着去绘画了。绘画是令人愉悦的,他们擅长绘画并且他们从中得到了一些满足他们灵魂的东西。然而他们中的一些人因为绘画而得到了奖励,所以他们的动机改变了。

Before they had been drawing because they enjoyed it, but now it seemed as though they were drawing for the reward. What they had been motivated to do intrinsically, they were now being given an external, extrinsic motivation for. This provided too much justification for what they were doing and so, paradoxically, afterwards they drew less.

之前他们绘画是因为他们喜爱这样做,但是现在他们好像是为了奖励而绘画的。以前他们是被内在的动机驱使的,而现在他们却被外在的动机驱动。这给了他们正在做的事情提供了很多理由,出乎意料的他们后来画的更少了。

This is the overjustification hypothesis for which Lepper and Greene were searching and although it seems like backwards thinking, it's typical of the way the mind sometimes works. We don't just work 'forwards' from our attitudes and preferences to our actions, we also work 'backwards', working out what our attitudes and preferences must be based on our current situation, feelings or actions (see also: cognitive dissonance).

这就是过度合理化假设,莱佩尔和格林一直研究的现象。尽管它看起来像是逆向思维,确实是思想工作的特定的方式。我们对行动的态度和热爱并不总是向前发展的,我们也会倒退,我们的态度和喜好是根据我们目前的情境、我们的感受或行动而定的。

When money makes play into work

当金钱把游戏变成工作

Not only this but rewards are dangerous for another reason: because they remind us of obligations, of being made to do things we don't want to do. Children are given rewards for eating all their food, doing their homework or tidying their bedrooms. So rewards become associated with painful activities that we don't want to do. The same goes for grown-ups: money becomes associated with work and work can be dull, tedious and painful. So when we get paid for something we automatically assume that the task is dull, tedious and painful—even when it isn't.

奖励是危险的还有另外的原因:因为它让我们看清我们的职责——被动的做我们不愿意做的事情。孩子们因为吃光他们所有的事物、完成他们的家庭作业或者整理好他们的卧室而得到奖励。所以奖励往往跟我们不愿意做的痛苦的事情一起发生。同样的情况也发生在成人身上:金钱往往伴随着工作,而工作往往是无趣沉闷又痛苦的。所以当我们做了某事而得到报酬的时候我们往往会不由自主的假定该任务是无趣沉闷又痛苦的事——即便任务本身并不是这样。

This is why play can become work when we get paid. The person who previously enjoyed painting pictures, weaving baskets, playing the cello or even writing blog posts, suddenly finds the task tedious once money has become involved.

这就是为什么当我们得到报酬的时候游戏变成工作的原因。当有金钱参与其中的时候,先前喜欢做画、织布、拉大提琴或写博客的人会突然发现工作是那么的沉闷无聊。

Yes, sometimes rewards do work, especially if people really don't want to do something. But when tasks are inherently interesting to us rewards can damage our motivation by undermining our natural talent for self-regulation.

是的,有时候奖励会有效果,特别是人们实在不喜欢做的事情。但是当任务本身是我们兴趣所在的时候,奖励却会通过破坏我们自我调节的天赋来破坏我们内在的动机。

www.psychspace.com心理学空间网