Alfred Binet – A truly applied

psychologist by Richard Howard*

Richard Howard on a psychologist who is remembered for educational testing, butwhose interests covered the full gamut of individual differences

_____________________________________________________________________

Citation: Howard, R. (2009). Alfred Binet: A truly applied psychologist. ThePsychologist, 22, 278–279.

_____________________________________________________________________

Alfred Binet, who died in Paris in 1911, will for ever be associated with intelligence testing, having developed the precursor of the Stanford–Binet IQ test, the Binet–Simon scale. Ironically he would have abhorred the idea of assigning a numericalvalue to a child’s mental capacity – his purpose in testing the intellectual capacity of school children was, he pointed out, to classify, not to quantify.

It is as a pioneer in the field of educational psychology that Binet tends to beremembered, largely due to the fact that his techniques for assessing mental (asopposed to chronological) age were exported to the United States and taken up byTerman. However, the aims and interests of Terman and Binet in relation to mental testing diverged considerably. In a commentary comparing Terman and Binet, HenryMinton (1998) pointed out that Binet saw the mental tests as diagnostic tools that could target such children for special compensatory education programmes that would improve their academic performance. They would even, in some cases, enable thesechildren to be channelled back to mainstream classrooms. Terman, on the other hand, was concerned with the need to identify the mildly retarded so that they could be segregated in special institutions.In the US, Binet’s techniques spawned an ‘educational testing’ industry that hasflourished ever since. Binet would have disapproved of the misuse to which his scale was put in the US, especially in the hands of members of the eugenics movement. The following quotation shows that Binet was primarily interested in what we wouldprobably nowadays call ‘social intelligence’:

It seems to us that in intelligence there is a fundamental faculty, the alteration or the lack of which, is of the utmost importance for practical life. This faculty is judgment, otherwise called good sense, practical sense, initiative, the faculty of adapting one’s self to circumstances. A person may be a moron or an imbecile if he is lacking in judgment; but with good judgment he can never be either. Indeed the rest of the intellectual faculties seem of little importance in comparison with judgment (Binet & Simon, 1916/1973,pp.42–43).

It is less widely appreciated that Binet’s interests covered the full gamut of individual differences, from deviant sexual interests – he originally coined the term ‘eroticfetishism’ (Binet, 1887) – through expert chess players, to chiromancers. This breadth of interest he combined with an experimental rigour that is exemplified in his work with schoolchildren on what we now call ‘interrogative suggestibility’. His interest in this topic probably reflected, in part, his early exposure to Charcot’s work onhypnosis at La Salpêtrière in Paris, which he abandoned to work at the Laboratory of Experimental Psychology at the Sorbonne (in his latter years, as its director). In part it also reflected his interest in the law – he graduated as a lawyer aged 21, anddeveloped a keen interest in psychology and the law. Indeed, he might equally becalled a pioneer of forensic psychology. He was well aware of the problems of faulty memory in relation to eyewitness testimony, whose reliability he questioned in his bookLa Suggestibilité, published in 1900 (this has never been translated into English, which accounts for its unfamiliarity to the Anglophone world).

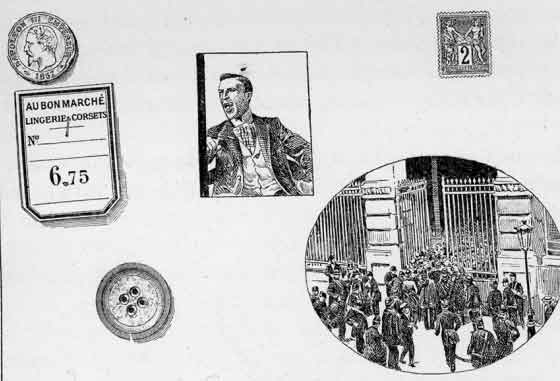

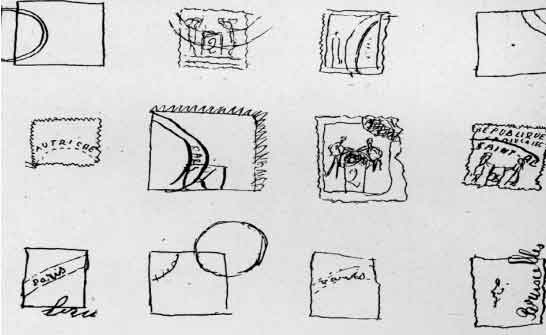

InLa SuggestibilitéBinet described a series of studies in which he manipulated, and measured, interrogative suggestibility in French schoolchildren. Using the technique of interrogative [279]pressure – ‘la memoire forcée’– both oral and written, Binet would present the child with simple objects such as those shown in Figure 1. Hewould then use suggestive questioning to induce memory errors. For example, thechild would be asked to reproduce, graphically, the two centimes stamp, indicating ‘the postmark that obscured the stamp’ (the stamp actually bore no postmark). The result was that many children would, under interrogative pressure, draw a stamp with a postmark, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Objects used by Binet in his forced memory procedure.

Figure 2. Evidence of interrogatory suggestibility in drawings of the objects. Children were asked to draw the postmark that obscured the stamp: in fact there was no such postmark.

Binet described two types of memory error – logical errors and errors of theimagination (‘erreurs d’invention’). In the first, there was a logical connection between the question and the child’s answer. For example, in response to the question ‘How was the button attached to the box?’ the child might answer ‘It was sewn on to the box with thread’. In the second type of error, the child would, through an act of the imagination, construct an object that, as Binet put it, had no visible relationship with reality. For example, in response to the suggestion that there was something on the button, the child would report that at its centre there was a sparkling diamond. This description of an invented or false memory was, some 75 years later, rediscovered by Loftus and co-workers, who described it as ‘imagination inflation’.

While Binet’s pioneering studies focused on both inter-individual variation ininterrogative suggestibility (the ‘Who?’ question) as well as on the possibleunderlying mechanisms (the ‘How?’ question), subsequent research has tended tofocus on one or the other. An individual differences approach has been adopted by Gudjonsson and others (see Gudjonsson, 2003, for a review), while an experimental approach has been pursued in the US by Loftus and colleagues (reviewed in Gerrie et al., 2004). Loftus and colleagues defined interrogative suggestibility as the extent to which people come to accept a piece of post-event information and incorporate it into their recollection. They have principally been concerned with the conditions under which leading questions are likely to affect the verbal accounts of witnesses. On the basis of studies in which subjects’ attention was manipulated, for example bydirecting their attention to misleading information, they concluded that interrogative suggestibility is mediated by a dysfunctional central cognitive mechanism, ‘discrepancy detection’. Were Binet alive today he would doubtless be using thetechniques of neuroscience to investigate the neural underpinnings of suggestibility (something I have attempted myself: see Howard & Chaiwutikornwanich, 2006)

In this era of increasing specialisation and fragmentation within our discipline, Binet stands out as an exemplar of what a psychologist perhaps ought to be. He was anautodidact – everything he knew about psychology he taught himself through hisreading in the French National Library – and his interests extended far beyondpsychology into the natural sciences. He was awarded a doctorate for his dissertation concerning the correlation between insects’ physiology and behaviour, and therefore qualifies as a psychophysiologist.

Despite his extensive studies and his prolific output – he wrote 13 books andnumerous articles on diverse topics – Binet was never offered a professorship in his own country. He did no teaching apart from a summer course in psychology at theUniversity of Bucharest. Here he seems to have been appreciated – the auditoriums where he taught were full to capacity, and he was offered a Chair in Psychophysiology. Would he have wanted himself to be typecast as an educationalpsychologist, as a forensic psychologist or as a psychophysiologist? I would argue that he would not – he would have wanted to be remembered as an applied psychologist in the broadest sense.

What was Binet like as a person? It is difficult to tell, since there are few if any personal accounts left by those who knew him. The product of a union between anartist and a medical doctor, he seems to have led an outwardly conventional life. He was apparently not particularly gifted as a child, but applied himself assiduously to the pursuit of his intellectual interests, aided by the financial support of a well-heeled family. In 1884 he married the daughter of an embryologist at the Collège de France, by whom he had two daughters. An accidental meeting on a railway platform in 1891 with Dr Henri Beaunis, then Director of the Experimental Psychology Laboratory at the Sorbonne, led to Binet asking him for a job, a request that Beaunis acceded to. This was arguably his lucky break, without which his later studies on interrogative suggestibility and mental testing might never have occurred.

In conclusion, it is appropriate to quote Terman’s assessment of Binet:

My favourite of all psychologists is Binet; not because of his intelligence test, which was only a by-product of his life work, but because of his originality, insight, and openmindedness, and because of the rare charm of personality that shines through all his writings. (Terman, 1932, p.331).

References

Binet, A. (1887). Le fétichisme dans l’amour [Fetishism in love]. Revue Philosophique, 24, 143–167.

Binet, A. (1900). L’interrogatoire. In La suggestibilité [Suggestibility] (pp.299–414). Retrieved 8

December 2008 fromwww.gutenberg.org/files/11453/11453-8.txt

Binet. A. & Simon, T. (1973). The development of intelligence in children. New York: Arno Press. (Original work published 1916)

Gerrie, M.P., Garry, M. & Loftus, E.F. (2004). False memories. In N. Brewer & K. Williams (Eds.) Psychology of law: An empirical perspective. New York: Guilford.

Gudjonsson, G.H. (2003). The psychology of interrogations and confessions. A handbook. Chichester: Wiley.

Howard, R.C. & Chaiwutikornwanich, A. (2006). The relationship of interrogative suggestibility to memory and attention. An electrophysiological study. Journal of Psychophysiology, 20(2), 79–93.

Minton, H.L. (1998). Commentary on: ‘New methods for the diagnosis of the intellectual level of subnormals’ Alfred Binet & Theodore Simon (1905); ‘The uses of intelligence tests’ Lewis M.

Terman (1916). Classics in the History of Psychology. Retrieved on 8 December 2008 from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Binet/commentary.htm© 2009/2012 The British Psychological Society

Terman, L.M. (1932). Lewis M. Terman: Trails to psychology. In C. Murchison (Ed.) History of psychology in autobiography (pp.297–331). New York: Russell & Russell._______________________________________________________________

www.psychspace.com心理学空间网